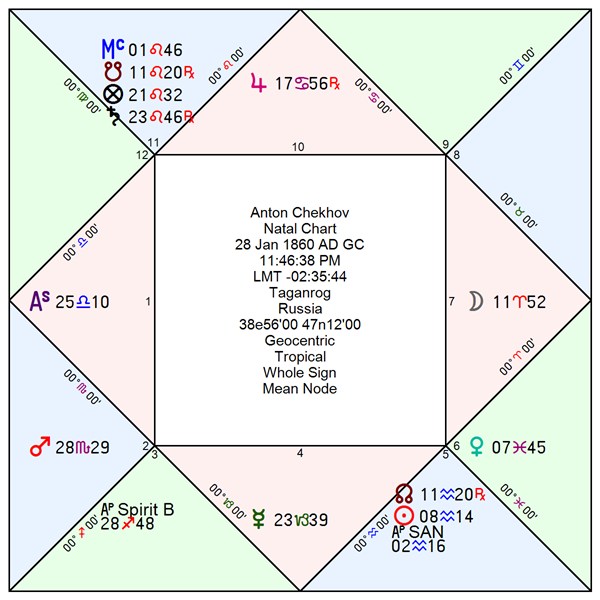

Anton Chekhov’s horoscope drops neatly into the Jupiter-in-Cancer series, but with a crucial twist: Jupiter is retrograde, and the Sun is in Aquarius. In this framework, Jupiter in Cancer signifies moral guardianship, patronage, land, farming, and the promise of care by those who “own” or oversee the social household—landowners, benefactors, officials, and cultural stewards. Turned retrograde, that promise inverts. The exalted figure of Jupiter-in-Cancer becomes hollowed out: moral authority erodes, guardians fail to protect, and stewardship of land curdles into mismanagement, debt, or decay. In practical terms, retrograde Jupiter behaves like Jupiter in Capricorn—the sign of loss, constriction, and the withering of inherited privilege—so what should nourish life instead presides over decline. Chekhov’s Sun in Aquarius sharpens this pattern into cool observation: he does not sermonize about moral collapse, but documents it with clinical clarity, letting institutional and agricultural failure reveal themselves through ordinary speech and small humiliations.

We’ve already seen this failed-farming, failed-stewardship theme recur in recent posts on Andrew Kehoe and Sharon Tate, where Jupiter-in-Cancer signatures likewise inverted into abandonment, decay, or the collapse of protective structures. Chekhov gives this same signature its most haunting literary expression. The sound of the axe chopping down the cherry trees at the end of The Cherry Orchard is one of the great symbols of failed guardianship in modern literature: an aristocratic estate that once promised continuity, care, and cultural memory is sold off and destroyed by those who inherit its hollowed-out authority. The orchard does not fall because of a villain, but because the landowners who should have protected it are too sentimental, impractical, or morally exhausted to act. What remains is not heroic tragedy but quiet erasure—the Jupiter-in-Cancer promise of care collapsing into Jupiter-in-Capricorn dispossession.

This Jupiter-retrograde pattern runs throughout Chekhov’s world: landowners who cannot manage their estates, doctors who cannot protect their patients, administrators who preside over systems already in moral retreat. When set beside Chekhov’s Moon’s Configuration—moving away from fragile warmth and toward fallen authority—the chart frames his art as the diagnosis of a culture living off inherited moral capital that no longer exists. Chekhov’s genius lies in showing how collapse happens without villains, how stewardship fails without rebellion, and how the exalted promise of care turns, retrograde, into the quiet sound of an axe in the orchard.

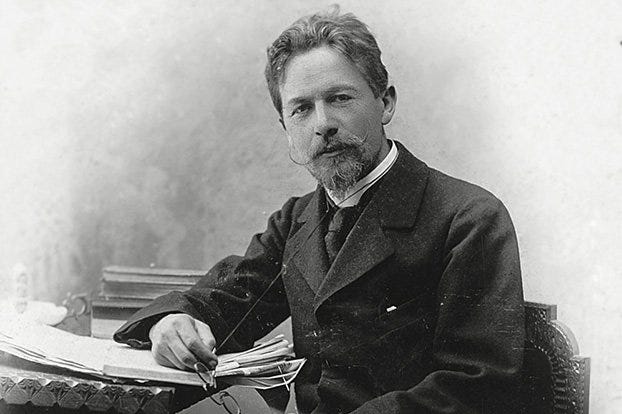

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov occupies a pivotal place in modern literature as the writer who taught fiction and drama how to listen to silence. Rather than building his stories around grand conflicts or moral lessons, Chekhov trained attention on what people fail to say, the small evasions of daily life, and the emotional costs of inaction. His work helped carry European literature out of 19th-century melodrama and into the psychological realism that would shape the 20th century.

Chekhov was born in the port town of Taganrog, into a family shaped by economic insecurity and emotional strain. His grandfather had been born a serf and purchased his freedom, and the family never quite escaped the psychological imprint of that history. Chekhov’s father, a strict and often cruel shopkeeper with intense religious habits, required long hours of labor and church service from his children. These early experiences left Chekhov with a lifelong sensitivity to humiliation, coercion, and the quiet tyrannies of everyday authority. When his father’s business collapsed, the family fled to Moscow, leaving Chekhov behind as a teenager to finish school alone and support himself through tutoring—an early apprenticeship in solitude and self-reliance that later surfaced in his detached narrative voice.

At Moscow University, Chekhov trained as a physician while simultaneously writing short comic pieces to keep his family afloat. What began as necessity evolved into a distinctive literary discipline. Medicine shaped how he looked at people: patiently, without sentimentality, attentive to symptoms rather than speeches. This clinical perspective became central to his art. Chekhov insisted that writers should not diagnose society in public or prescribe moral cures; their task was to describe life honestly and let readers draw their own conclusions. His letters outline an aesthetic of brevity, precision, originality, and compassion—an ethic of observation rather than judgment. This stance angered critics who wanted literature to serve political or moral programs, but it allowed Chekhov to create a fiction of rare psychological neutrality.

By his late twenties Chekhov was already widely read, winning major literary prizes and the respect of senior figures such as Tolstoy and Gorky. Yet his growing reputation coincided with a deepening unease about the complacency of Russian society and the ease with which cruelty hides behind routine. His stories increasingly focused on provincial towns, minor officials, bored landowners, and people who sense that their lives have gone wrong but cannot summon the will to change them. Tragedy, in Chekhov’s world, rarely arrives with fireworks; it unfolds quietly, embedded in habit, delay, and resignation. The terror of Ward No. 6 is not ideological oppression but the ease with which indifference becomes institutionalized and sanity itself becomes vulnerable to bureaucratic violence.

In 1890, Chekhov undertook an arduous journey across Siberia to the penal colony of Sakhalin Island. There he interviewed prisoners and settlers, compiling thousands of data points on conditions of exile and forced labor. The resulting book combined social investigation with moral witness, marking one of the most serious documentary efforts by a major writer of the period. The trip took a toll on his health, but it reinforced his commitment to looking directly at suffering rather than aestheticizing it. Around the same time, he settled at his estate in Melikhovo, where he balanced writing with medical service to local peasants, famine relief efforts, and public health work during epidemics. This mixture of private literary labor and quiet civic responsibility mirrors the ethical restraint of his fiction: engaged with suffering, but resistant to theatrical gestures of virtue.

Chekhov’s transformation of modern drama came after early failures nearly drove him from the theater. Working with Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre, he developed a new kind of play in which the most important events occur between lines of dialogue rather than within them. The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters, and The Cherry Orchard dismantle the machinery of traditional plot, replacing it with mood, interruption, miscommunication, and the slow revelation of emotional stalemate. Characters speak of change while remaining frozen in place; humor and despair coexist in the same breath. Social change enters not as revolution but as erosion—the old order cut down tree by tree, almost apologetically.

Chekhov’s later years were shaped by tuberculosis, which forced him into periods of exile abroad and eventual residence in Yalta. The physical narrowing of his world coincided with an emotional deepening in his late stories, which explore love, compromise, and the cost of choosing safety over transformation. His marriage to the actress Olga Knipper was affectionate but largely lived at a distance, reinforcing one of the central tensions of his work: intimacy constrained by circumstance. When Chekhov died at forty-four, he left behind no manifesto, no school of doctrine—only a body of work that taught later writers how to register the inner weather of ordinary lives.

Chekhov’s enduring influence lies in his refusal to provide moral closure. His people are not heroes or villains; they are stalled, uncertain, intermittently lucid about their own disappointments. By allowing lives to remain unresolved, Chekhov helped invent the emotional grammar of modern realism, where meaning arises not from decisive action but from the long, quiet pressure of what is endured.

Rodden Rating B, Bio/autobiography, 29-Jan-1860, 12:10 AM, ASC 29LI29

Proposed Rectification: 28-Jan-1860, 11:46:48 PM, ASC 25LI10’39”

Complete biographical chronology, rectification and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model Factors favoring Mercury/Capricorn

· Bound ruler: Lot of Fortune, Prenatal Syzygy (Eclipse)

· Angular in 4th house

Physiognomy factors favoring Libra, Gemini

· Face appears a mix of the compressed ovate (Libra) and the elongated shape (Gemini). Gemini rising decans often wear corrective eyewear.

Moon’s configuration

Phase I – Moon separating from the Sun (Aquarius, 4th/5th houses)

Delineation. The Moon separating from the Sun describes an early emotional movement away from warmth, harmony, and aesthetic pleasure into a life shaped by duty, strain, and bodily vulnerability. The Sun is in Aquarius in the bound of Venus, so whatever solar vitality and sense of purpose exist are filtered through Venusian themes of pleasure, intimacy, and aesthetic sensitivity. The bound ruler Venus is in Pisces, placed in the 5th house by quadrant houses and in the 6th house by whole sign houses, situating pleasure and intimacy at the crossroads of creativity and illness, delight and bodily consequence. This configuration makes warmth real but fragile: affection, beauty, and sensuality are present, yet they do not provide lasting protection from hardship. The Moon’s separation from this Venus-colored Sun establishes a core tension in the life—tenderness is available, but it cannot shield the native from strain, and the body becomes one of the places where emotional costs are paid.

Biographical match. Chekhov’s early life reflects precisely this separation from fragile warmth. His childhood household combined moments of maternal gentleness and cultural sensitivity with paternal cruelty, religious severity, and economic stress. Whatever Venusian warmth existed in the home was real but overwhelmed by fear, obligation, and exhaustion. Later in life, Chekhov’s pursuit of pleasure and intimacy coexisted with chronic illness and bodily depletion. While there is no evidence that sexual encounters caused his tuberculosis, his life nonetheless reflects the Venus-in-the-6th pattern: pleasure and tenderness are continually shadowed by physical vulnerability, fatigue, and the steady intrusion of illness. The Moon’s separation from a Venus-colored Sun marks the emotional departure from the hope that intimacy might shield one from suffering.

Phase II – Moon applying to Jupiter (Cancer, retrograde, 9th/10th houses)

Delineation. The Moon’s application to Jupiter retrograde in Cancer draws the emotional life toward figures and institutions that present themselves as protective, paternal, or morally authoritative, yet are already in decline. Jupiter in Cancer signifies guardianship, patronage, and the promise of care from those in high social or moral position; retrograde, this promise turns inward and collapses, revealing hollow benevolence, compromised ethics, and authority that can no longer sustain what it claims to protect. The Moon’s movement toward this Jupiter does not indicate faith in reform or confidence in institutional renewal, but repeated emotional contact with failing structures of care and guidance. What is encountered is not cruelty for its own sake, but the quiet erosion of moral legitimacy among those who still occupy positions of dignity and power.

Biographical match. Chekhov’s life and work repeatedly engage with this pattern of paternal authority already in retreat. As a physician, he encountered institutional neglect and bureaucratic indifference masquerading as care; as an observer of Russian society, he documented the moral exhaustion of officials, doctors, landowners, and administrators who retained social standing while losing ethical credibility. His journey to Sakhalin placed him face-to-face with a penal system that claimed corrective purpose yet functioned as a machinery of quiet brutality. Across his stories and plays, figures of authority appear dignified in form but inwardly spent, protective in rhetoric but incapable of genuine guardianship—an exact biographical and literary echo of the Moon’s application to Jupiter retrograde in Cancer.

Interpretive Summary

Chekhov’s Moon separates from a Venus-inflected Sun, indicating an early withdrawal from fragile warmth and aesthetic consolation into a life shaped by strain, duty, and bodily vulnerability, where pleasure exists but cannot shield the native from hardship. The Moon then applies to Jupiter retrograde in Cancer, drawing emotional life toward paternal figures and institutions that claim moral authority yet are already hollowed out from within. Together, these phases describe a psyche formed by the loss of reliable intimacy and the repeated confrontation with failed guardianship, producing not a revolutionary temperament but a diagnostician of quiet institutional decay. Chekhov’s art emerges from this configuration as a sustained witness to the erosion of warmth in private life and the collapse of moral credibility in public life, rendered with compassion but without illusion.

Influence of Sect

In Chekhov’s nocturnal chart, Jupiter and Saturn fall out of sect, weakening the stability of benefic authority and intensifying the harshness of paternal constraint. Jupiter in Cancer, though exalted by sign, is further marginalized by being out of sect and retrograde, reinforcing the theme that figures who ought to protect, patronize, or embody moral dignity instead appear diminished, compromised, or already in decline. This accords closely with Chekhov’s lifelong preoccupation with fallen authorities—doctors who become indifferent, administrators who preside over cruelty, landowners whose social status masks ethical exhaustion. Saturn, also out of sect, sharpens the severity of Saturn-signified paternal dynamics, intensifying experiences of discipline, repression, and emotional coldness in the early household and reinforcing Chekhov’s sensitivity to quiet tyranny and moral rigidity in positions of domestic or institutional power. By contrast, Venus in Pisces and Mars in Scorpio are both in sect, giving greater efficacy to the instincts of desire, intimacy, and embodied striving. Venus in Pisces—exalted and operating from her own bound—elevates Chekhov’s Venusian themes into the cultural mainstream: tenderness, erotic longing, compassion, and aesthetic sensitivity are not marginal in his work but central to how his characters experience suffering and connection. This helps explain why romantic and emotional longing in Chekhov’s stories resonated broadly rather than remaining confined to subcultural or decadent registers. Mars in Scorpio in sect, placed at the threshold of the 2nd house, gives disciplined, sustained drive in material and survival matters rather than reckless aggression; it points less to violence than to endurance, labor under pressure, and the capacity to extract livelihood from demanding conditions. Biographically, this fits Chekhov’s relentless work ethic—his ability to produce large volumes of writing while practicing medicine, supporting his family, and engaging in public service—suggesting that his financial security and professional standing were built not through patronage or status (the fallen Jupiter theme), but through sustained personal effort, bodily exertion, and practical skill.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

Although Chekhov was born just after a New Moon, which under the Early/Late Bloomer model should incline toward early blooming, his life pattern stubbornly refuses to cooperate with that expectation. He lived only about 44 years, placing the midpoint of his life around age 22, but his creative authority and cultural importance consolidate well after that point: his national reputation emerges in his late twenties, his Sakhalin journey and moral turning point arrive around age 30, and his greatest plays and most enduring stories are written in his thirties and early forties. Before the midpoint, what we see is not flowering but survival—precocious responsibility, financial pressure, and relentless labor rather than recognized vocation. Framed this way, Chekhov stands as a genuine counterexample to the Early Bloomer thesis rather than a convenient eclipse exception: even when the Moon has separated from the Sun, the timing of his life’s flowering still falls decisively in the second half, reminding us that Moon-phase models capture tendencies, not destinies, and that in certain lives—especially those shaped by illness, duty, and institutional decay—other forces in the chart can override the expected rhythm of early versus late development.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.