Benjamin Franklin is often called the first American—not because he was chronologically first, but because he seems to anticipate what Americans would later become. He was industrious, practical, improvisational, civic-minded, suspicious of inherited authority, and relentlessly focused on what works. Like most Americans after him, Franklin gets an enormous amount done—far more than can be responsibly introduced in a single Substack post.

So rather than attempt a comprehensive portrait, I want to focus this opening section on two astrological themes that quietly organize Franklin’s life and explain why his influence was so durable:

(1) Jupiter in Cancer at acronychal rising, and

(2) Venus in Capricorn as the victor of the horoscope, operating in mutual reception with Saturn in Taurus.

Together, these describe a man who becomes a moral representative of the people while simultaneously mastering the arts of legitimacy, structure, and long-term authority.

Jupiter in Cancer at Acronychal Rising: The Moral Visibility of the Common Man

Jupiter in Cancer, when operating directly, has long been associated with moral philosophy, populist leadership, and an intuitive grasp of collective feeling. It is a placement that speaks for households, communities, and the “common good,” rather than for elites or abstract principles. Historically, it often appears in figures who act as moral spokesmen rather than commanders—figures who persuade, reassure, and represent rather than rule.

Franklin’s Jupiter is retrograde, which ordinarily complicates or internalizes Jupiter’s expression. But here an important exception applies. Jupiter is at acronychal rising, the moment of maximum brilliance in the night sky, when a superior planet reappears as an evening star. At this phase, visibility overrides introversion. What has been internalized becomes public; what has been delayed becomes authoritative. In effect, Jupiter insists on being seen.

The result is a Jupiter that does not manifest as doctrinal preaching or charismatic domination, but as widely trusted moral presence—a figure people instinctively believe speaks for them. This quality is drawn forth most clearly during Franklin’s major 12-year Jupiter Firdaria period from 1757 to 1769, when he served as colonial agent in London. During these years, Franklin did not merely lobby Parliament; he became the symbolic representative of American grievances. Colonists trusted him to speak on their behalf precisely because he seemed to embody moderation, fairness, and common sense. His authority did not come from office or force, but from credibility rooted in shared values.

This is Jupiter in Cancer doing what it does best: articulating collective sentiment, protecting communal interests, and translating moral feeling into persuasive public speech—made fully visible through acronychal rising.

Venus in Capricorn as Victor: Legitimacy, Structure, and Durable Authority

If Jupiter explains why Franklin was trusted, Venus in Capricorn explains why his influence lasted.

In my work, Venus in Capricorn functions very differently from more familiar Venus placements. This is not Venus as pleasure, romance, or aesthetic indulgence. It is Venus as legitimacy, status, and social authorization—the capacity to make relationships durable, contracts binding, and cooperation stable over time. In Franklin’s chart, Venus is the victor of the horoscope, meaning that value, persuasion, and consent ultimately govern outcomes more decisively than force or ideology.

Crucially, this Venus operates in mutual reception with Saturn in Taurus, linking attraction to structure and persuasion to endurance. What Venus draws together, Saturn stabilizes. What Saturn limits, Venus renders acceptable. The result is a distinctive life pattern: conflict is not eliminated, but managed; danger is not defeated, but organized; power is not seized, but legitimized.

This is why Franklin consistently appears not as a warrior or ruler, but as a broker—of institutions, treaties, civic projects, scientific societies, loans, arms, and alliances. His success lies in making cooperation work under real-world constraints. He does not overpower opposition; he outlasts it.

I treat this Venus–Saturn mutual reception in much greater depth in a separate post, “A Glimpse of AGI – how ChatGPT ups the ante on sect and mutual reception,” where I compare Franklin’s configuration with those of Dick Cheney, Karl Jaspers, and Eva Braun, all of whom share the same underlying structure but express it very differently. Readers interested in the full theoretical treatment can go there; here, it is enough to note that Franklin’s authority rests on legitimate value embedded in durable systems.

Two Themes, One Life

Taken together, these two themes explain a great deal. Jupiter in Cancer at acronychal rising makes Franklin a trusted moral representative of the people. Venus in Capricorn, reinforced by Saturn, allows that trust to crystallize into institutions, agreements, and long-lasting authority. One explains his visibility; the other explains his permanence.

In the sections that follow, we’ll see how these principles repeat across Franklin’s life—sometimes quietly, sometimes spectacularly—but always with the same underlying logic: persuasion over force, structure over impulse, and legitimacy over spectacle.

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) was one of the most versatile and influential figures of the eighteenth century, distinguished not by mastery of a single field but by an unusual capacity to translate ideas into practical social, political, and institutional forms. Born in Boston to a large family of modest means, Franklin left formal schooling early and was apprenticed to his brother’s printing business. From the outset, his life followed a pattern of self-education, disciplined labor, and gradual accumulation of credibility. His early break from Boston and resettlement in Philadelphia marked the first of many acts of self-reinvention, setting the tone for a career defined less by inherited status than by earned authority.

Franklin achieved early prosperity as a printer, editor, and publisher, most notably through the Pennsylvania Gazette and Poor Richard’s Almanack. The almanac, issued annually for over two decades, made Franklin widely known throughout the colonies as a purveyor of maxims, proverbs, and moral counsel. Its aphorisms—on industry, frugality, prudence, and moderation—helped shape a shared language of practical ethics among ordinary readers. Rather than preaching doctrine, Franklin offered concise rules for living that aligned private behavior with social stability, reinforcing his reputation as a spokesman for common sense and everyday virtue.

As his financial independence grew, Franklin increasingly redirected his energies toward civic improvement. He played a central role in founding institutions that addressed concrete social needs: lending libraries, fire companies, insurance associations, hospitals, and educational initiatives that eventually became the University of Pennsylvania. These projects reflected a consistent philosophy: public welfare could be advanced through voluntary cooperation, practical organization, and incremental reform rather than through inherited authority or coercive power. Franklin’s influence expanded not through office-holding but through his ability to convene people, articulate shared interests, and design workable systems.

Franklin’s scientific work further elevated his standing, particularly his experiments with electricity in the 1740s and early 1750s. His investigations were notable not only for their originality but for their emphasis on demonstrable results and practical application. Inventions such as the lightning rod, the Franklin stove, and bifocal lenses embodied his belief that knowledge should alleviate danger, discomfort, and inefficiency. International recognition followed, and Franklin became one of the most celebrated natural philosophers in Europe, a status that later proved politically consequential.

His political career emerged gradually from this foundation of public trust. During the crises surrounding imperial taxation—most notably the Stamp Act—Franklin was repeatedly selected by colonial assemblies to represent their interests in Britain. He was chosen not as a firebrand or ideologue, but as a figure whose moderation, credibility, and understanding of British political culture made him an effective intermediary. In testimony before Parliament and in private negotiations, Franklin framed colonial grievances in moral and practical terms, appealing to shared values rather than revolutionary rhetoric. His role during this period established him as a “people’s envoy,” a representative whose authority rested on persuasion and legitimacy rather than force.

As tensions escalated toward revolution, Franklin’s position evolved from imperial reformer to advocate of independence, though he remained cautious in tone. During the Revolutionary War, his diplomatic mission to France was decisive. In Paris, Franklin combined symbolic presence with patient negotiation, cultivating public sympathy while quietly arranging loans, arms supplies, and eventually a formal alliance. His role in securing weapons, financial support, and military assistance was crucial to the American war effort. Here again, Franklin functioned less as a commander than as a **broker—of alliances, resources, and confidence—**operating effectively within complex international systems.

In his later years, Franklin returned to America as a figure of near-universal respect. He served at the Constitutional Convention, where his advanced age and reputation allowed him to act as a stabilizing presence rather than a partisan leader. His interventions emphasized compromise, restraint, and the dangers of ideological rigidity. Even when he disagreed with specific provisions, Franklin consistently argued that durable political structures required mutual concession and broad consent.

Franklin’s final public commitments reflected a continued concern with moral responsibility and social cohesion. As president of an abolitionist society in Pennsylvania, he lent his authority to petitions against slavery, framing the issue in terms of justice, humanity, and national character. Though he did not live to see the resolution of these questions, his late advocacy underscored a lifelong pattern of ethical development rather than static virtue.

Throughout his life, Franklin cultivated an image—and a reality—of usefulness. He preferred influence to command, legitimacy to charisma, and persuasion to coercion. Whether publishing moral maxims, inventing practical devices, organizing civic institutions, negotiating arms and alliances, or representing collective interests before foreign powers, Franklin consistently operated as a mediator between individual needs and collective order. His legacy lies not in any single achievement but in his sustained ability to align practical intelligence with public trust.

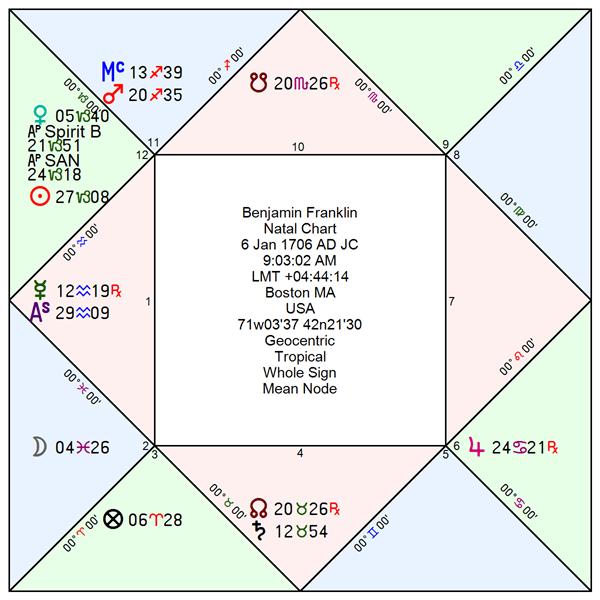

Rodden Rating: DD, Conflicting;unverified, 10:30 AM, ASC 7AR21

Revised Rectification (2020): 9:03:02 AM, ASC 29AQ09’55”

Note: Chart above is presented for 6-Jan-1706, Old Style Julian Calendar. The equivalent New Style Gregorian Calendar birthdate is 17-Jan-1706.

Complete biographical chronology and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model Factors favoring Venus/Capricorn

· Bound ruler of MC, Moon, Lot of Fortune, Lot of Spirit

· Mutual reception with Saturn/Taurus by sign

Physiogonomy Model factors favoring Aquarius, Capricorn

· Aquarius rising sign: broad forehead, shaped like bull dozer’s blade

· Libra rising decan ruler (Venus/Capricorn): facial descriptions of Franklin in middle age describe his face as round, roughly consistent with the oval signs of all cardinal signs in Willner’s facial shape-sign model.

Moon’s Configuration

Benjamin Franklin’s Moon separates from Mars and applies to Venus, but the configuration is complicated by three critical factors: (1) the Moon and Mars are both in mutable signs, (2) the separation from Mars is out of sign and followed by a void-of-course interval, and (3) the Moon’s application to Venus draws Saturn into the configuration through mutual reception by sign. As a result, the Moon’s configuration does not describe a simple chronological progression from conflict to ease, but a repeating pattern of disruption followed by increasingly effective mediation.

Because both the Moon and Mars are in mutable signs, the problems signified by Mars recur throughout life rather than being confined to an early phase. What changes over time is not the presence of Mars, but the quality of the response represented by Venus.

Phase I: Moon in Aquarius Separating from Mars

Delineation. The Moon separating from Mars indicates a life repeatedly exposed to disruptive, volatile, or dangerous conditions that originate outside the native’s control. Mars, as the out-of-sect malefic, signifies hazards that are not merely personal but collective: conflict, fire, ideological strife, and violence.

The Moon in Aquarius does not respond to Mars through personal aggression. Instead, it experiences Mars as a social problem—something affecting communities, systems, or shared environments. Franklin does not embody Mars; he encounters Mars as a condition requiring response. The separation shows that Franklin does not identify with martial force, but neither does he escape it. Mars initiates crises; Franklin survives them.

Phase II: Void-of-Course Moon and Sign Change to Pisces

Delineation. Following its separation from Mars, the Moon enters a void-of-course interval before changing signs. This signifies a period in which direct action is ineffective and immediate resolution is unavailable. The native cannot confront Mars directly, nor can he eliminate its effects. Instead, there is a pause, withdrawal, or suspension of agency.

The sign change from Aquarius to Pisces marks a fundamental shift in strategy. Rather than responding through collective organization alone, the Moon adopts a more adaptive, mediating posture. Pisces dissolves rigid oppositions and seeks indirect solutions. This phase describes Franklin’s characteristic refusal to meet force with force, choosing instead delay, redirection, humor, negotiation, or institutional workaround.

Phase III: Moon Applying to Venus

Delineation (Expanded). The Moon’s application to Venus describes the resolution mechanism of the entire configuration. Venus is the victor of the horoscope, meaning that value, legitimacy, persuasion, and social cohesion ultimately govern the life’s outcomes. However, Venus does not act alone.

Venus is in Capricorn and in mutual reception by sign with Saturn in Taurus. This means that Venus operates with Saturn’s resources, authority, and structural capacity, while Saturn in turn acts in service to Venusian aims. Pleasure, harmony, and attraction are subordinated to durability, order, and institutional form. The beneficence promised by Venus is therefore not indulgent or emotional, but practical, contractual, and enduring.

As the Moon applies to Venus, it carries the memory of Mars forward into a Venus–Saturn solution space. Threats are not eliminated; they are managed, contained, and reorganized. The outcome is not peace through victory, but stability through design. Over time, this produces a life in which conditions ease—not because dangers vanish, but because the native becomes increasingly skilled at transforming conflict into structure.

Interpretive Note on Repetition

Because the Moon and Mars are both in mutable signs, this configuration does not describe a linear life arc in which Mars dominates early life and Venus dominates later life. Instead, the same Mars–Venus pattern repeats across different domains and periods. What evolves is the sophistication and effectiveness of the Venusian response, not the disappearance of Mars.

Illustrative Mars–Venus Pairings

The following examples illustrate how the same Moon configuration repeats across Franklin’s life, each time expressing the same underlying pattern.

Fire → Organized Fire Prevention. Mars signifies fire as an uncontrolled and destructive force. Franklin repeatedly encountered fire as a civic hazard rather than a personal threat. The Venus–Saturn response was not heroic intervention but systematic mitigation: organized fire companies, insurance mechanisms, and the Franklin stove, which transformed fire from danger into regulated utility. The problem persists; the response improves.

War and Violence → Arms Procurement and Diplomacy. Mars also signifies warfare and weapons, particularly in foreign contexts. Franklin does not act as a soldier or commander. Instead, he becomes a broker—arranging arms, financing, and alliances through negotiation and trust. Venus supplies relationship and persuasion; Saturn supplies contracts, logistics, and long-term obligation. Violence is not erased, but redirected into controlled channels.

Ideological Conflict → Institutions and Compromise. Mars in Sagittarius further signifies ideological and philosophical conflict. Franklin encounters this through censorship, imperial disputes, and revolutionary pressures. His Venusian response is not polemic but institution-building: newspapers, assemblies, treaties, and constitutional frameworks. The goal is not ideological purity, but social coherence.

Interpretive Summary of the Moon’s Configuration

Benjamin Franklin’s Moon configuration describes a life repeatedly shaped by disruptive forces that are never fully resolved, yet progressively mastered. Mars initiates danger; Venus, acting with Saturn, designs stability. As a result, the native’s life does not become conflict-free with age, but it becomes easier, more authoritative, and more secure, as each recurrence of Mars is met with a more effective Venusian solution.

Influence of Sect

In Benjamin Franklin’s day chart, sect plays a decisive role in shaping how the Moon’s configuration operates in practice. With Mars and Venus both out of sect, the Moon’s separation from Mars and application to Venus does not describe a gentle movement from difficulty to ease, but a configuration that is exaggerated at both ends. Mars, as the out-of-sect malefic, signifies crises that are sharper, more extreme, and more socially disruptive than they might otherwise be—fires, war pressures, ideological conflict, and material danger that arrive with real force. Venus, also out of sect, does not simply soothe these conditions; her response can be excessive in its own way. Venus in Capricorn, when unsupported, can verge on an overinvestment in legitimacy, reputation, and social standing, even a kind of lust for status or recognition that overshoots moderation. However, in Franklin’s chart this tendency is decisively modified by Venus’s mutual reception with Saturn in Taurus, the in-sect malefic. Saturn’s in-sect status gives it regulatory authority, and through reception it disciplines Venus, cooling excess desire and translating Venusian aims into durable, practical forms. As a result, the Moon’s application to Venus does not resolve Mars through indulgence or ambition, but through structure, organization, and restraint.

Beyond the Moon’s configuration itself, sect also elevates Jupiter, the in-sect benefic, whose placement allows Franklin’s influence to extend broadly across society. Jupiter’s in-sect condition increases his reach, credibility, and appeal to ordinary people, enabling him to function repeatedly as a trusted representative of collective interests. In this way, sect explains why Franklin’s life contains both intensified crises and unusually effective responses: Mars and Venus exaggerate the problem and the impulse to respond, while Saturn and Jupiter—by virtue of being in sect—ensure that those responses mature into authority, trust, and lasting public usefulness rather than personal excess.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

Benjamin Franklin was born shortly after a New Moon, placing him firmly in the waxing Moon category. According to the early/late bloomer thesis, waxing Moon natives are early developers: they show initiative sooner, gain traction earlier in life, and begin shaping their identity and direction before their peers. On first glance, Franklin appears to complicate this thesis, since his most celebrated political and diplomatic achievements occur in later life. However, a closer examination shows that Franklin actually fits the waxing Moon model quite well—provided we distinguish between early activation and late culmination.

Franklin’s life shows unmistakable signs of early momentum. He left formal schooling young, entered apprenticeship early, broke with his brother while still in his teens, and established himself as an independent printer and publisher by his early twenties. By his mid-twenties, he already exercised public influence through the Pennsylvania Gazette; by his thirties, he was widely known through Poor Richard’s Almanack; and by his forties, he had achieved financial independence and international scientific recognition. These are not the markers of a late bloomer. They reflect a waxing Moon pattern in which initiative, self-direction, and outward engagement begin early and compound steadily.

What can create the illusion of late blooming in Franklin’s case is the nature of the arenas in which he later excelled. Diplomacy, moral authority, and representative leadership are domains that reward accumulation rather than sudden emergence. Franklin’s most famous roles—as colonial agent in London, revolutionary diplomat in France, and elder statesman of the Constitutional era—require prior credibility, trust, and symbolic weight. These are not skills that appear suddenly; they are built on decades of earlier public visibility, institutional involvement, and social usefulness. In other words, Franklin’s later prominence is not a delayed start, but the harvest of an early and continuously developing trajectory.

The Moon’s post–New Moon phase also aligns with Franklin’s lifelong orientation toward building, expanding, and adding rather than withdrawing or refining. His career is characterized by accumulation—of skills, institutions, alliances, and influence—rather than by the stripping-away or late-life reversal often seen in waning Moon lives. Even when Franklin’s activities shift in tone with age, they do not represent a second beginning so much as a broader application of capacities developed early.

In sum, Franklin supports the early/late bloomer thesis rather than undermining it. His waxing Moon indicates early activation and outward momentum, while the apparent lateness of his greatest achievements reflects the Saturnian and institutional nature of the roles he ultimately occupied. Franklin is best understood not as a late bloomer, but as an early starter whose influence required time to fully mature, a distinction that preserves the integrity of the waxing/waning Moon framework.

AI Notice: This post created with assistance from ChatGPT.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.