Chester Alan Arthur (1829-1886)

Death by Lightning: The Machine Politician Who Dismantled the Machine

Chester A. Arthur is the most misunderstood figure in the constellation of James Garfield’s presidency. Remembered, if at all, as Roscoe Conkling’s pliant lieutenant who stumbled into the White House after an assassin’s bullet, Arthur is usually cast as either a machine politician who improbably reformed himself or as a cipher who drifted into history. Both readings miss what makes him interesting. Arthur was not weak; he was formed inside institutions. His power was never theatrical. It was administrative—learned in logistics, refined in patronage, and ultimately repurposed under the pressure of office. To understand Arthur is to understand how bureaucratic skill can precede moral transformation, and how a presidency can force a man trained to serve machines to begin dismantling one.

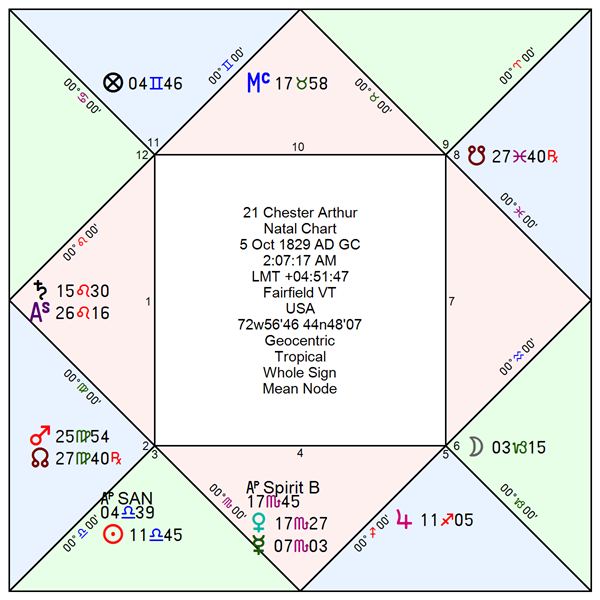

Arthur’s horoscope makes this institutional formation legible. With Leo rising and the Moon in the 6th house, his life is organized around clerks, subordinates, and the management of daily operations rather than charismatic command. The Moon’s separation from Mars in Virgo describes an early formation in disciplined service and logistics; its later application to Mercury in Scorpio shows those same techniques repurposed into coercive accounting and revenue extraction at the New York Custom House—the “pound of flesh” exacted by clerks on goods passing through the port. The Moon’s change of sign from Sagittarius to Capricorn marks the pivot from mobile service to durable office: campaign work gives way to hierarchy, routine, and institutional permanence. Arthur does not invent the machine; he becomes fluent in how to run it.

Sect sharpens the drama of Arthur’s political relationships. In a nocturnal figure, Saturn and Jupiter are out of sect, leaving Saturn in Leo—aptly signifying Roscoe Conkling—as the harsher presence in Arthur’s life: prideful, domineering, and personally punishing in its demands of loyalty. By contrast, Mars and Venus are in sect, tempering the stress of administration and giving Arthur a cooler, more measured style under pressure (Mars in Virgo), while allowing his aesthetic tastes and cultural preferences to circulate widely (Venus in Scorpio), from the Victorian refashioning of the White House to the Tiffany windows that helped define its public image. What follows is not a story of a man who awakens late to virtue, but of a man whose early formation in disciplined administration is finally turned—under the shock of Garfield’s assassination—toward reform, breaking with the very machine that made him.

Chester Alan Arthur was the accidental reformer of the Gilded Age—a machine politician elevated by patronage who, once in office, helped begin dismantling the system that made him. Trained as a New York lawyer, Arthur’s early career included work on high-profile cases touching public rights: in 1854–55, as a junior partner in the firm of Culver, Parker & Arthur, he argued the lawsuit brought by Elizabeth “Lizzie” Jennings, the Black schoolteacher forcibly ejected from a segregated Manhattan streetcar. Jennings’ victory helped push New York City streetcars toward desegregation, an episode often read as a striking predecessor—in structure if not scale—to Rosa Parks’ later challenge to segregated transit a century later. In private life, Arthur married Ellen (“Nell”) Herndon, a socially prominent Virginian whose connections and grace complemented his rise; her sudden death from pneumonia in January 1880 devastated him just before the vice-presidential campaign that would place him one heartbeat from the presidency.

Arthur’s political ascent came through the Stalwart faction of the New York Republican Party as the loyal lieutenant of Senator Roscoe Conkling, whose power radiated from the New York Custom House—the most potent patronage engine in the nation. As Collector of the Port of New York, Arthur effectively marshalled the Custom House workforce on behalf of Conkling’s machine, benefiting directly from the spoils system’s blend of salary, status, and leverage: thousands of federal jobs, factional discipline, and the ability to reward loyalty and punish dissent. Arthur was not the architect of Conkling’s empire so much as its polished administrator—well suited to managing networks of loyalty rather than waging ideological war—and Conkling’s influence helped elevate him onto the national ticket in 1880 as a vice-presidential “balance” for the party. Temperamentally, the partnership paired opposites: Conkling was choleric—domineering, theatrical, and driven to command—while Arthur was phlegmatic-sanguine—affable, conflict-avoidant, and comfortable operating within hierarchy. The imbalance explains both Arthur’s long deference and the manner of the eventual break: Conkling escalated and demanded loyalty; Arthur withdrew and reoriented his loyalties to the office itself.

The rupture came with President James Garfield’s assassination in 1881 by an office-seeking fanatic who believed himself entitled to a patronage reward—an event that turned spoils politics into a public scandal stained with blood. As president, Arthur faced a legitimacy crisis and an institutional test: remain the client of a faction, or become the steward of the state. He surprised the country by breaking—quietly but decisively—from Conkling’s orbit and backing civil service reform, culminating in the Pendleton Act of 1883 and the first durable federal move toward merit-based hiring. The pivot was less the awakening of a lifelong crusader than the transformation of a patronage man by circumstance, public outrage, and the moral gravity of office: Arthur didn’t betray Conkling theatrically; he simply stopped being available to him. He left office without a personal machine and died only a year later, but his presidency remains one of the era’s great ironies—a man formed by the spoils system who helped begin its undoing.

Arthur’s presidency also left three other durable marks on the early administrative state, two constructive and one morally dark. First, he presided over a significant modernization of the U.S. Navy, signing legislation that launched the “New Navy” with steel-hulled, steam-powered warships, nudging the United States away from post–Civil War naval decay toward the foundations of later American sea power. Second, Arthur took an unusually independent stance against congressional logrolling and fiscal excess, vetoing the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1882 as an egregious pork-barrel measure—even though Congress overrode him—thereby signaling a conception of the presidency as a check on legislative patronage spending rather than its facilitator. Third, and most troublingly, Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the first major federal law to bar immigration on racial and national grounds. Although he had initially vetoed a harsher version of the bill as a violation of treaty obligations and basic fairness, he ultimately accepted a “compromise” exclusion statute under intense political pressure. The episode exposes the limits of Arthur’s reformist conscience: capable of breaking with a patronage boss and backing institutional modernization, yet still willing to ratify racial exclusion when it aligned with prevailing political winds. Taken together—civil service reform, naval modernization, resistance to pork-barrel spending, and the sanctioning of exclusionary immigration law—Arthur’s record reveals a presidency defined less by ideology than by reluctant stewardship: a man shaped by machine politics who nonetheless helped lay early foundations for a more institutional, bureaucratic, and globally oriented American state, even as he bore responsibility for one of its most enduring injustices.

Astrodatabank Rodden Rating A, from memory, 6:08 AM based on “sun-up” recollection, ASC 12LI04

2022 Revised Rectification: 2:07:16 AM, ASC 26LE16’20”

Complete biographical chronology, rectification and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model Factors favoring Mars/Virgo

· Sign ruler: Lot of Spirit

· Bound ruler: Ascendant

· Mutual reception by sign with Mercury/Scorpio

· Conjunct North Node

· Dynamic activity: Mars/North Node directed to the Ascendant timed his Civil War Service which he said was the happiest time of his life

Physigonomy Model Factors favoring Leo

· Rising sign is Leo, rectanguler-shaped in Willner’s facial shape sign model. Arthur qualifies on this shape; in addition, hair is curly – mimicking the Sun’s rays. Finally, the overall appearance is leonine.

· Rising decan is Aries ruled by Mars/Virgo. This does not appear a match.

Moon’s Configuration

Phase I – Moon separating from Mars (Virgo, 2nd house)

Delineation. The Moon in Sagittarius signifies motion, travel, dispersal, and engagement with wide-ranging affairs, foreigners, distant campaigns, and matters conducted away from one’s habitual place. As the Moon separates from an out-of-sign square to Mars in Virgo, the lunar function moves away from a period of strain produced by Mars’s Virgoan significations: toil, drill, constraint, labor under command, and the management of details under pressure. The square indicates friction and exertion; being out of sign, the connection is indirect and mediated rather than fully consonant. Mars in Virgo is not the Mars of battlefield glory but of service, logistics, regulation, and the burdens of orderly labor. The Moon’s separation describes withdrawal from a phase of enforced discipline, routine constraint, and exacting service obligations.

Biographical register. This phase accords with Arthur’s period of Civil War service as a quartermaster. The Moon in Sagittarius fits the experience of movement, distance from home, and participation in extended campaigns and supply networks rather than fixed civic administration. Mars in Virgo describes the laborious, procedural character of quartermaster work: provisioning, accounting, discipline of men and materials, and service under bureaucratic constraint. The separating square marks this as a completed period of strain and exertion rather than a lifelong condition, even as its methods remain available for later reuse.

Phase II – The Moon changes sign: Sagittarius → Capricorn

Delineation. The Moon’s change of sign marks a change in the condition and mode of operation of the lunar significations. In Sagittarius, the Moon is oriented toward movement, dispersion, and affairs conducted across distances; in Capricorn, the Moon is placed in a sign of Saturn, emphasizing constraint, hierarchy, endurance, and subjection to institutional structures. Capricorn is the Moon’s detriment: the Moon’s significations are narrowed, burdened, and subjected to necessity, duty, and long-term obligation. The sign change therefore describes a shift from mobile, outward-facing service to settled, hierarchical administration within enduring structures. What had been episodic or campaign-based becomes routinized, fixed, and bound to office.

Biographical register. This phase fits Arthur’s transition from wartime service into peacetime institutional life. The Moon’s move into Capricorn describes emotional and practical accommodation to bureaucracy, hierarchy, and the slow, enduring rhythms of office-holding. The life of movement and temporary service gives way to permanent placement within institutions—clerks, offices, chains of command, and durable administrative machinery. The Moon in Capricorn signifies habituation to constraint and to operating within hierarchical systems rather than episodic mobilization.

Phase III – Moon applying to Mercury (Scorpio, 4th house)

Delineation. With the Moon in Capricorn applying by sextile to Mercury in Scorpio, the lunar significations of employees, subordinates, and daily administration are brought into workable coordination with Mercury’s Scorpio significations of accounting under threat of penalty, enforcement, surveillance, and coercive extraction. The sextile shows facility and practical cooperation rather than compulsion. Mercury’s rulership of the 11th house of the King’s Money, and its governance of the Lot of Fortune, place revenue, state finance, and the management of flows to the treasury at the center of this application. The mutual reception by sign between Mars in Virgo and Mercury in Scorpio links the earlier discipline of labor (Mars/Virgo) to the later techniques of extraction and enforcement (Mercury/Scorpio). The Moon’s application does not discard the earlier martial logic; it reorganizes it into a fiscal-administrative register.

Biographical register. This phase corresponds closely to Arthur’s management of the New York Custom House. The Moon in Capricorn describes clerks and employees operating within rigid hierarchy and durable office structures. Mercury in Scorpio describes the forensic, coercive, and penalty-backed administration of tariffs—the “pound of flesh” exacted through inspection, valuation, and enforcement. Because Mercury rules the 11th and holds the Lot of Fortune, Arthur’s wealth and advancement flow through the King’s Money: revenue collection and the distribution of state funds. The mutual reception indicates that the procedural discipline learned in military logistics is carried forward into civilian administration: quartermaster methods become customs enforcement techniques, with Mars’s discipline now expressed through Mercurial accounting and extraction.

Interpretive Summary

The Moon’s configuration describes a continuity of disciplined service carried forward into durable institutional administration and finally into the monetized enforcement of state revenue. The separating out-of-sign square from Mars in Virgo marks a completed period shaped by labor, drill, and procedural constraint among clerks and subordinates (Moon in the 6th), while the Moon’s change of sign from Sagittarius to Capricorn signals a shift from mobile, campaign-based service to settled life within hierarchy, duty, and enduring bureaucracy. The subsequent application of the Capricorn Moon to Mercury in Scorpio by sextile brings this habituated discipline into practical coordination with coercive accounting and enforcement, and with Mercury ruling the 11th house of the King’s Money and holding the Lot of Fortune, revenue flows become central to livelihood and advancement. The mutual reception between Mars in Virgo and Mercury in Scorpio links the earlier regime of logistics and drill to the later regime of fiscal extraction, showing how techniques learned in managing labor and supplies are repurposed within customs administration and revenue collection.

Influence of Sect

In this nocturnal figure, sect sharpens the interpersonal and institutional dynamics of the Moon’s configuration by aggravating the malefic most implicated in Arthur’s political antagonisms while moderating the operational pressures he faced in administration. Saturn, being out of sect and placed in Leo, is correspondingly harsher in its effects and aptly signifies Conkling as a domineering, prideful authority whose influence bears more cruelly upon Arthur than it would in a diurnal chart; Jupiter is likewise out of sect and therefore offers little reliable mitigation or protection here, functioning weakly as a benefic and failing to provide a stabilizing counterweight to Saturnian pressure. By contrast, Mars and Venus are both in sect, which materially softens and regularizes the Moon’s configuration: Mars in Virgo operates with cooler, more measured discipline under stress, describing Arthur’s capacity for controlled, procedural management rather than volatile reaction, while Venus in Scorpio, though in detriment, gains sect support and thus achieves broader social reach, fitting the public diffusion of his aesthetic and cultural preferences, such as the Victorian redecoration of the White House and the embrace of Tiffany windows as nationally legible taste. Mercury’s sect is typically derived from its nearest planetary association rather than treated independently; here, drawn into Venus’s orbit, Mercury is effectively in sect as well, which helps explain why the Customs House regime of fees and charges—though coercive in mechanism—was widely regarded in its time as a normal and legitimate business practice rather than naked extortion, aligning administrative extraction with socially accepted Venusian norms of exchange and value.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

Tested against the early/late bloomer thesis, Arthur fits the early-bloomer profile tolerably well, though with an important caveat about what “blooming” means in a career built inside institutions rather than through sudden personal distinction. Born after a New Moon, the model predicts that formative structures and early vocational pathways should consolidate relatively early in life, with the later years marked more by stewardship and culmination than by first emergence. Arthur’s pattern aligns with this: his professional identity and operational competencies—law practice, wartime quartermaster administration, and then rapid embedding within New York’s patronage machinery—were established by midlife, long before the presidency unexpectedly arrived. His rise into consequential power was thus not the discovery of a new vocation late in life but the culmination of capacities and networks formed early; the presidency itself functions less as a “late bloom” than as a sudden elevation of an already-formed administrative persona into a new scale of responsibility. The model holds here insofar as Arthur’s decisive skills and career trajectory were set early, even if his public moral redefinition (civil service reform) occurred later under the pressure of circumstance rather than as a delayed flowering of talent.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.