Évariste Galois (1811–1832)

When the Moon of law and equality strays into the house of passion, even genius must duel with fate

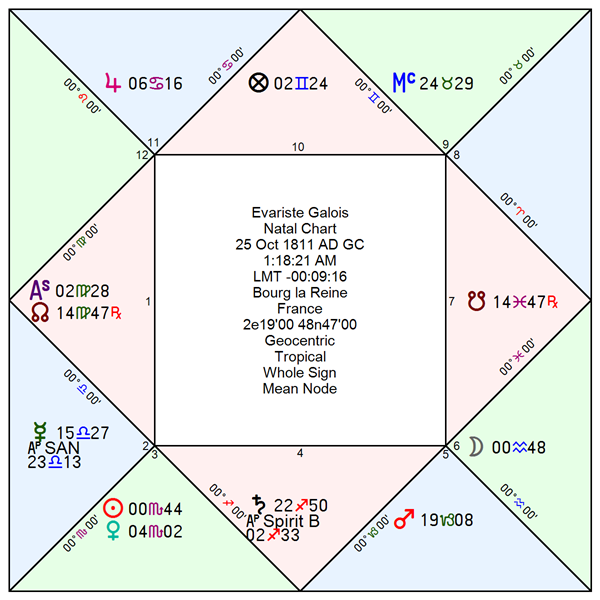

Évariste Galois lived and died like an equation solved too early. Born under a Moon in Aquarius—a sign devoted to rules, structure, and equality—his intuition was tuned to the impersonal beauty of law. In that same impulse to abstract order, he founded what we now call group theory, discovering the hidden symmetries of algebra. Yet the Moon’s path in his horoscope tells a story of light gained and lost: an early brilliance (Moon separating from the Sun), the promise of allies that turn away (Jupiter retrograde in Cancer), and finally the pull of Venus in Scorpio—passion, rivalry, and contagion that derailed his life’s purpose.

The duel that killed him at twenty was not only a social tragedy but a celestial one: the Moon caught between intellect and desire, unable to reach its promised trine to Mercury, victor of the horoscope and emblem of mathematical reason. Only after death did that trine perfect itself—when Liouville published his papers and the world at last spoke Galois’s language. His chart reads like his mathematics: every disruption eventually resolves into a symmetry.

Évariste Galois was born on October 25, 1811, in Bourg-la-Reine, near Paris. A brilliant but rebellious student, he discovered mathematics through independent reading rather than formal study, devouring the works of Lagrange and Legendre at a precocious age. His teachers at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand quickly realized that his mind operated on a level far beyond the curriculum. Galois twice failed the entrance examinations to the École Polytechnique—not for lack of ability, but because his temperament was impatient with conventional methods and examiners whom he deemed intellectually inferior. In 1829, he was admitted instead to the École Normale (then called the École Préparatoire), where he continued his independent research.

During this period, Galois produced the manuscripts that would change the course of modern mathematics. His papers sought to explain the conditions under which algebraic equations can be solved by radicals—an issue dating back to Renaissance mathematicians. In the process, he discovered deep relationships between equations and the symmetries of their roots, introducing the notion of a group of permutations, a concept that would later become central to algebra, geometry, and physics. His results provided a decisive answer to the long-standing question of why general fifth-degree equations cannot be solved by radicals, extending and clarifying the earlier insights of Niels Henrik Abel.

Yet Galois’s intellectual brilliance was matched by his political passion. A fervent Republican opposed to the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe, he became active in radical student societies. His outspokenness and defiance of authority earned him multiple arrests in 1831, including one for a provocative toast calling for the king’s death. His political notoriety alienated many within the conservative academic establishment, further isolating him from the institutions that might have supported his mathematical career.

Galois’s relationship with the Académie des Sciences was fraught and tragic. His principal submission, addressing the solvability of equations, was first lost, then resubmitted in 1831 for evaluation by Siméon Denis Poisson. Poisson’s report—declaring the memoir “neither sufficiently clear nor sufficiently developed to permit us to judge its correctness”—was devastating. He found Galois’s work incomprehensible, a verdict that reflected not malice but genuine bafflement at its originality. Galois had introduced new concepts and notations without sufficient exposition, leaping from idea to idea with revolutionary speed. The rejection mirrored the consensus of his contemporaries: Galois’s manuscripts were simply too far ahead of their time.

Aside from the brief and tentative encouragement of Augustin-Louis Cauchy, who recognized Galois’s promise but failed to shepherd his work through publication, he had no champions within the French mathematical establishment. His sharp temperament, youthful arrogance, and political entanglements made him a difficult figure to support publicly. By the time of his final imprisonment in 1831, he was effectively an intellectual exile—an unrecognized genius working in isolation.

On the night of May 29, 1832, the eve of a fatal duel—possibly over a woman named Stéphanie-Félicie du Motel, though some suspect political intrigue—Galois spent his last hours feverishly summarizing his theories in a letter to his friend Auguste Chevalier. He implored that his work be read and judged by competent men. Shot in the abdomen the next morning, he died in a Paris hospital on May 30, 1832, at the age of 20.

It took more than a decade for his work to be understood. In 1846, Joseph Liouville, editor of the Journal de mathématiques pures et appliquées, rediscovered Galois’s manuscripts and published his Mémoire sur les conditions de résolubilité des équations par radicaux, recognizing its genius. Liouville’s endorsement transformed Galois’s reputation overnight—from obscure radical to foundational thinker. Later mathematicians such as Camille Jordan expanded his ideas into a full-fledged group theory, establishing Galois as a central figure in the modern algebraic tradition.

Today, Galois is celebrated not only for his mathematical breakthroughs but also for his uncompromising spirit—a symbol of the romantic genius misunderstood by his age. His tragic life encapsulates the gulf that can exist between intellectual innovation and institutional comprehension. What Poisson dismissed as “incomprehensible” became, within a generation, the language through which modern mathematics speaks.

Rodden Rating AA, BC/BR in hand, 1:00 AM, ASC 29LE09

Proposed Rectification: 1:18:21 AM, ASC 2VI28’46”

Complete biographical chronology and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model factors favoring Mercury in Libra

Sign ruler of Ascendant and Lot of Fortune

Bound ruler of Ascendant, Moon, and Lot of Fortune

Morning rising solar phase

Received by exaltation (Saturn)

Received by bound (Jupiter)

Physiognomy factors favoring Virgo

Shape of the face is dominated by a pointed chin which is a classic Virgo characteristics. Galois has none of the bulk, strength, and sexual magnetism one would expect with Leo rising + Sun/Scorpio based on Astrodatabank data. (see Picasso for this configuration of Leo rising + Sun/Scorpio).

Moon’s Configuration

The aspect sequence is as follows

1. Moon Aquarius Ingress

2. Moon square Sun

** Birth Moment**

3. Jupiter stationary retrograde

4. Moon square Venus

5. Moon trine Mercury

Phase I – The Moon in Aquarius (Fixed Air, 6th House)

The Moon in Aquarius orients intuition toward fixed laws, axioms, and impersonal order. It is emotional distance turned into intellectual precision. Placed in the 6th house, it operates as a disciplined craft of mind—the tireless repetition and refinement behind a theory. Galois’s emotional life expressed itself through structure: equations, symmetries, and the logic of substitution.

Because Aquarius stands opposite Leo, sign of monarchy and privilege, this Moon naturally resists hierarchy. Its instinct is egalitarian and collective—mirroring both his devotion to mathematical equality and his republican politics. This lunar condition makes the native more faithful to principle than to circumstance. It gives him his clarity, but also his solitude.

Phase II – Moon Separating from the Sun (Scorpio, 3rd House)

The Moon’s recent separation from the Sun describes an early surge of visibility and acclaim that does not endure. The Sun in Scorpio in the 3rd house signifies presence within the immediate community—public reputation built through intensity, debate, and defiance. At the outset, this connection between Sun and Moon shows promise: flashes of recognition for a prodigy who impressed his teachers at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand and briefly captured attention within Parisian academic circles. Yet as the Moon moves away, the light of approval fades. The separation marks the loss of protection—fame without continuity. What began as curiosity about a brilliant youth gives way to misunderstanding. His name is noticed, then dismissed. The lunar light wanes; the Sun’s favor recedes.

Phase III – Interlude of Jupiter Retrograde in Cancer (11th House)

Between the Moon’s separation from the Sun and its application to Venus, Jupiter retrograde intervenes. Normally exalted in Cancer and placed in the 11th house, Jupiter would promise patronage, collegial alliances, and institutional shelter. Retrograde, it withholds them.

This planet represents the learned community—the academies, examiners, and professors who might have confirmed his genius. Its reversal records how that promise turned backward: enthusiasm turning to incomprehension, opportunity to rejection. Here lie the failed examinations, the lost memoirs, and Poisson’s judgment that his paper was “neither clear nor developed enough to judge.” The goodwill implied by Jupiter in the 11th is undone by its motion: the community retreats while Galois advances. The result is isolation at the precise moment he needed recognition.

Phase IV – Moon Applying to Venus (Scorpio, 3rd House)

After the collapse of collegial support, the Moon turns toward Venus in Scorpio. Venus here signifies attraction entwined with danger—desire that contaminates what it touches. In the 3rd house it governs the neighborhood, the circle of comrades and rivals. This application coincides with the turbulence of 1832: political agitation, imprisonment, and the fatal duel. Venus in Scorpio converts passion into crisis; the intellect’s detour into jealousy and personal entanglement.

Its symbolism extends to the body. Venus in the sign of the genitals and lower waters connects to the cholera epidemic sweeping Paris, an affliction spread through corruption of fluids—another echo of Venus’s taint in Scorpio. Thus, instead of reaching Mercury’s rational equilibrium, the Moon is pulled downward into Venusian intensity. The mathematician’s cool logic is consumed by emotional contagion.

Phase V – Posthumous Application to Mercury (Libra, 2nd House)

Only after death does the Moon’s light complete its journey to Mercury in Libra, the Victor of the Horoscope. Mercury in Libra signifies equivalence, balance, and notation—the very spirit of equality embodied in mathematical signs. In life, this trine was obstructed by passion and rejection; in death, it perfects. When Joseph Liouville published Galois’s papers in 1846, the Moon’s delayed application found its resolution: the public intellect (Mercury) received what the living community had refused. This final aspect restores proportion. The Moon’s Aquarian devotion to law at last joins Mercury’s language of proof. His work, once dismissed as “incomprehensible,” becomes the foundation of modern algebra—the symmetry completed beyond the limits of his lifetime.

Interpretive Summary

The Moon in Aquarius gives Galois an emotional need for logic and order, yet its sequence of aspects tells a story of light gained, lost, and recovered. First – promise and notice (Sun); next – betrayal by colleagues (Jupiter Rx); then – consumption by passion (Venus); and finally – posthumous restoration through intellect (Mercury). His life thus enacts the very structure he discovered: relationships of transformation that achieve closure only when the final symmetry is perceived. The group of his own existence—each element inverted, opposed, and reconciled—completes itself after his death.

AI Notice: ChatGPT contributed to this article.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.