J. D. Salinger (1919-2010)

Jupiter’s Acronycal rising and the Reckoning of a Phony World

On July 16, 1951, The Catcher in the Rye was published and quickly became one of the most widely read—and debated—novels in postwar America. Within a few years it was both a commercial success and a cultural lightning rod, widely adopted in high school and college English curricula even as it provoked anxiety among parents, educators, and moral guardians. Its timing was crucial. The early 1950s marked a moment of intense social consolidation in the United States: the rise of suburban conformity, corporate identity, Cold War loyalty tests, and a growing emphasis on respectability and social order. Yet beneath this surface stability ran a current of unease, particularly among the young, who sensed that something vital had been sacrificed in the name of security.

Salinger’s novel gave voice to that unease. Holden Caulfield’s alienation, moral disgust, and obsession with protecting innocence resonated with a generation coming of age in a culture that prized conformity while quietly fearing its psychological cost. This same cultural mood soon found expression in other icons of youthful disaffection, most notably James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955), which dramatized similar anxieties about authority, authenticity, and emotional abandonment. The Catcher in the Rye did not create this mood so much as articulate it with unusual moral clarity. Its extraordinary reception reflects not merely literary success, but a deeper alignment with the emotional and ethical contradictions of postwar American life—a resonance that astrology, particularly through the lens of sect and lunar phase, helps to illuminate.

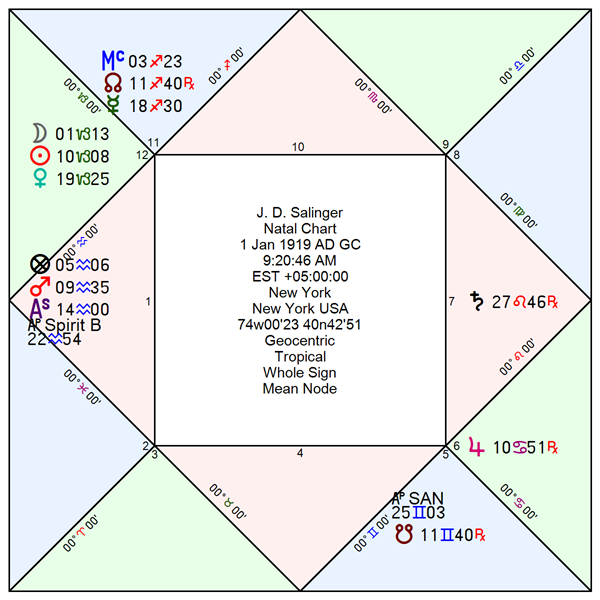

How is this dynamic shown astrologically? The answer lies with Jupiter in Cancer retrograde, the victor of Salinger’s chart. Ordinarily, a retrograde planet behaves as though it were placed in the opposite sign, so Jupiter in Cancer would tend to operate like Jupiter in Capricorn—emphasizing discipline, hierarchy, and institutional authority rather than care or emotional protection. But this inversion does not remain stable. As Jupiter approaches acronychal rising, it begins to recover its native condition, allowing Jupiter-in-Cancer themes to reassert themselves precisely at the point of confrontation with the dominant social order. What emerges is not a gentle sentimentalism, but a moral challenge: the values of care, innocence, and emotional truth pressing back against a world organized around status, conformity, and control.

Crucially, Jupiter in Salinger’s chart is in sect, meaning it operates in alignment with the majority temperament of the society in which he lived. In sect doctrine, planets that are in sect speak for the collective; their significations resonate broadly rather than marginally. This explains why The Catcher in the Rye did not remain a niche or countercultural text but became a mass phenomenon. Its critique of “phoniness” succeeded not because it opposed the culture from the outside, but because it articulated what a large portion of the public already felt but could not yet name. Jupiter’s beneficence here is not comfort but recognition: the book gave voice to a widespread unease with postwar conformity, corporate identity, and moral compromise. Because Jupiter was in sect, that unease circulated easily, moving through schools, families, and institutions themselves, turning a private moral protest into a generational touchstone.

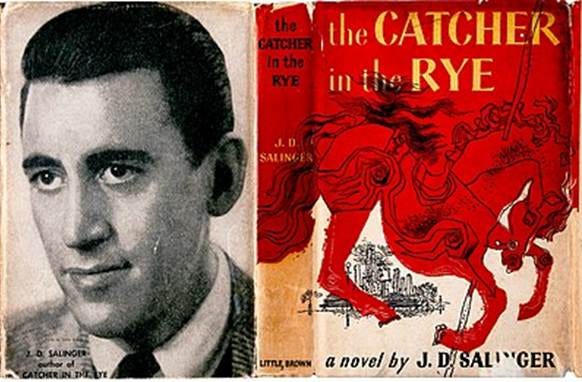

J. D. Salinger (1919–2010) was an American writer whose brief but seismic literary career reshaped postwar American fiction and whose later withdrawal from public life became almost as influential as his work itself. Born Jerome David Salinger in New York City to a Jewish father and a mother who converted from Christianity, he grew up in a divided cultural and religious household that later informed his recurring themes of alienation, moral absolutism, and spiritual longing. After an unsettled early education—including time at Valley Forge Military Academy—he studied writing at Columbia University under Whit Burnett, editor of Story magazine, who published Salinger’s earliest professional work and helped shape his precise, voice-driven prose.

Salinger’s relationship with The New Yorker became a significant author–magazine partnership in American literary history. After early rejections, the magazine published “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” in 1948, introducing Seymour Glass and inaugurating a long association that would define Salinger’s public reputation. Throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, The New Yorker became the primary venue for his fiction, including many Glass family stories and, indirectly, the cultural runway for The Catcher in the Rye (1951). The magazine’s prestige, editorial standards, and cultivated audience aligned closely with Salinger’s own desire for artistic control and moral seriousness, even as he grew increasingly resentful of publicity and interpretation.

Salinger’s formative years as a writer were deeply entangled with World War II. Drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942, he served in the Counterintelligence Corps, a role that combined linguistic aptitude, psychological assessment, and interrogation. He landed on Utah Beach on D-Day, fought through the Battle of the Bulge, and advanced with Allied forces into Germany. Remarkably, he continued writing throughout the war, carrying early drafts of The Catcher in the Rye with him in his pack and publishing stories in American magazines while still on active duty. His exposure to combat, mass death, and the moral collapse of Europe left lasting psychological effects; after Germany’s surrender, he participated in intelligence work connected to denazification and was present during the period surrounding the Nuremberg Trials. Shortly thereafter, he suffered what would now likely be diagnosed as PTSD and spent time in a military hospital—an experience that deepened the spiritual and emotional withdrawal evident in his postwar writing.

The publication of The Catcher in the Rye in 1951 made Salinger both famous and deeply uneasy. The novel’s adolescent voice—angry, wounded, morally alert—resonated profoundly with postwar youth and quickly became emblematic of generational alienation. Yet Salinger recoiled from celebrity, increasingly retreating from public life while continuing to write. His later stories, particularly those centered on the Glass family (Franny and Zooey, Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters, and Seymour: An Introduction), shifted away from social realism toward spiritual inquiry, Eastern philosophy, and inward moral struggle. After 1965, he ceased publishing entirely, though evidence suggests he continued writing privately for decades.

Salinger’s personal relationships were complex and often troubling. He married three times: first to Sylvia Welter (1945–1947), a German woman he met during the war; then to Claire Douglas (1955–1967), with whom he had two children, Margaret and Matthew; and finally to Colleen O’Neill (1988–1997). Alongside these marriages, Salinger maintained a pattern of intense romantic relationships with much younger women, several of whom were teenagers at the time they met him. These relationships—most notably with Joyce Maynard and Jean Miller—have since become a significant and controversial part of his legacy, raising difficult questions about power, idealization, and control that echo the psychological dynamics explored in his fiction.

In his final decades, Salinger lived reclusively in Cornish, New Hampshire, fiercely guarding his privacy and refusing interviews, photographs, or public commentary. He became a symbolic figure: a writer who rejected literary celebrity, commodification, and public interpretation in favor of personal discipline and spiritual inwardness. When he died in 2010 at age 91, he left behind a paradoxical legacy—an author whose influence was immense, whose silence was deliberate, and whose work continues to shape conversations about authenticity, trauma, and the cost of artistic purity.

Rodden Rating X, Date without time

Proposed rectification 9:20:46 AM, ASC 14AQ00’17”

Complete biographical chronology, rectification and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor of the Horoscope – Jupiter/Cancer – retrograde

· Sign ruler of MC

· Bound ruler of ASC, MC, and Lot of Spirit

· Approaching acronycal rising

Physigonomy factors favoring Aquarius, Gemini

· Rising sign/Aquarius: Shape of forehead is rectangular, the shape of a bull dozer’s shovel.

· Rising decan/Gemini: Shape of face is elongated, a match to Willner’s facial shape model for Gemini. Also the shape of the nose is long and straight, a trait also assigned to Gemini

Moon’s Configuration

Phase I — Moon Separating from Saturn (Leo, retrograde, 7th House)

Delineation. Saturn in Leo retrograde functions here as Saturn in Aquarius: the imposition of collective ideology, moral systems, and mass allegiance presented as ethical necessity. In the 7th house, this Saturn signifies confrontation with public authority, ideological adversaries, and coercive social structures. Its retrograde condition inverts allegiance, producing resistance rather than obedience. The Moon’s separation from Saturn marks a withdrawal from ideological participation itself—an exit from systems that demand moral submission under the guise of collective good.

Biographical Match. Salinger’s wartime service placed him directly inside such systems. As a counterintelligence officer moving through occupied Europe, he encountered not only violence but the bureaucratic moral machinery of National Socialism—an extreme manifestation of Saturn-in-Aquarius logic. His exposure to the concentration camps and postwar intelligence work forced confrontation with ideology as an instrument of dehumanization. The Moon’s separation from Saturn reflects his rejection of all mass moral projects thereafter. Rather than replace one ideology with another, Salinger withdrew from political identification altogether, cultivating a lifelong skepticism toward movements, causes, and institutional righteousness.

Phase II — Moon Enters Capricorn (Bound of Mercury, 12th House)

Delineation. As the Moon enters Capricorn, emotional life becomes disciplined, contained, and inwardly governed. Placed in the 12th house, this restraint operates away from public visibility, favoring privacy, silence, and self-command. The bound ruler, Mercury, introduces a shaping intelligence: feeling is processed through language, craft, and conscious control. Yet Mercury is in Sagittarius—youthful, idealistic, philosophical—infusing this otherwise austere configuration with vision and moral aspiration. The result is a mind that disciplines emotion without extinguishing idealism, converting feeling into reflective, ethical inquiry.

Biographical Match, This configuration mirrors Salinger’s postwar life as a writer who combined rigorous control with moral idealism. His prose—precise, clipped, and disciplined—was nevertheless animated by a youthful ethical seriousness. His long association with The New Yorker reflects Mercury’s editorial precision, while the Sagittarian quality behind it explains the persistent search for meaning, innocence, and moral clarity beneath the surface restraint. His retreat to Cornish, New Hampshire, exemplifies the 12th-house withdrawal: not retreat from conscience, but the cultivation of inner order as a form of ethical life.

Phase III — Moon Applying to Opposition of Jupiter (Cancer, retrograde, 6th House)

Delineation. The Moon’s application to Jupiter introduces a moral counterweight. Jupiter in Cancer is exalted, signifying care, protection, and emotional truth, yet its retrograde motion and 6th-house placement constrain its expression. As discussed in the recent essay on Jupiter’s acronychal rising, this configuration permits a temporary re-emergence of Jupiter’s beneficence even while its full social authority remains blocked. The opposition creates tension rather than integration: moral feeling confronts a world incapable of sustaining it.

Biographical Match. This tension animates The Catcher in the Rye. Holden Caulfield embodies Jupiter in Cancer’s protective impulse—his desire to preserve innocence is sincere and uncompromising. Yet the retrograde condition renders this impulse socially unworkable. Holden cannot reform the world; he can only protest it. Salinger’s moral vision thus remains intensely felt but structurally unsupported. His compassion expresses itself through narrative witness rather than action, critique rather than reform.

Notable Configuration — Waning Moon Under the Sunbeams

Delineation. The waning Moon under the Sun’s beams signifies withdrawal from visibility and the relinquishing of public agency. This is not defeat but renunciation: the conscious dimming of presence after meaning has been articulated. The Moon’s light is absorbed rather than extinguished, indicating a choice to withdraw from recognition once purpose has been fulfilled.

Biographical Match. Salinger’s disappearance from public life after 1965 embodies this condition with rare purity. Having articulated his moral and artistic vision, he withdrew from publication, interviews, and literary society. His silence was not exhaustion but principle. In choosing obscurity, he preserved the integrity of his work, allowing it to stand apart from authorial persona or institutional mediation.

Interpretive Summary

Salinger’s Moon describes a life shaped by confrontation with collective ideology, followed by disciplined withdrawal and moral interiorization. His rejection of mass systems did not produce cynicism but a demanding ethical solitude, in which innocence became a private value rather than a social program. The tension between Jupiter’s moral generosity and Saturn’s ideological gravity defines his work: compassion without naïveté, conscience without institution. His eventual disappearance was not retreat from meaning but the final expression of it—an insistence that some truths must remain unperformed.

Influence of Sect

Salinger’s chart is diurnal, which places the dominant planets of the configuration—Saturn and Jupiter—in sect, meaning they operate with the support of the prevailing collective mood rather than in tension with it. In sect theory, planets in sect do not merely function more smoothly; they represent values and experiences that the majority of society is prepared to recognize, legitimize, and absorb. Saturn’s role therefore reflects not private alienation but a broadly shared postwar reckoning with authoritarianism. In the wake of World War II, American society collectively rejected the excesses of Nazi totalitarianism, and this moral reckoning gave Saturn’s themes—discipline, conscience, limits, and judgment—a culturally sanctioned form. Salinger’s confrontation with the moral consequences of ideological obedience thus resonated widely because it mirrored a collective ethical reckoning already underway.

Jupiter’s role further explains the extraordinary reception of The Catcher in the Rye. As a benefic in sect, Jupiter amplifies and disseminates its themes across the social body. Jupiter in Cancer—despite its retrograde condition—articulates a protective, sentimental, and morally charged concern for innocence, belonging, and emotional safety. In the early Cold War period, this translated into a widespread anxiety about conformity, suburbanization, and the moral formation of youth. Catcher succeeded not because it rebelled against society, but because it voiced a fear already widely shared: that adults had become compromised and that children required protection from a hollowed-out moral order. The novel’s mass appeal—and enduring presence in school curricula—reflects this in-sect amplification. Its message aligned with what the culture was already prepared to feel, making Salinger’s private moral vision legible and persuasive to millions.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

J. D. Salinger was born January 1, 1919 and died January 27, 2010, giving him a lifespan of just over 91 years. The midpoint of his life therefore falls around mid-1964. According to the Early/Late Bloomer model, a post–Full Moon birth should correlate with major creative realization in the second half of life, clustered around or after this midpoint. Yet Salinger’s decisive literary achievements occur well before it: The Catcher in the Rye (1951, age 32), the Glass family stories throughout the 1950s, and his final published work in 1965, when he was 46—just at the midpoint itself. After that, no new public work followed. By any conventional measure of literary productivity and cultural influence, Salinger was an early bloomer, not a late one. His case therefore contradicts the predictive core of the Early/Late Bloomer thesis.

Attempted Reconciliation via the Moon under the Sunbeams

The only partial reconciliation lies in the Moon’s condition rather than its phase. Salinger’s waning Moon is also under the Sun’s beams in the 12th house, a configuration traditionally associated with withdrawal, concealment, and loss of public agency. While this does not rescue the timing prediction of the model, it does explain the form his later life took. Rather than flowering creatively in maturity, Salinger’s second half is defined by disappearance—by silence as vocation. In this sense, the Moon’s waning phase does not describe delayed productivity but deliberate retreat. His life suggests a refinement of the thesis: for some waning-Moon natives, especially those with a combust or hidden Moon, the second half of life fulfills itself not through achievement but through withdrawal from visibility altogether.

AI Notice: This post created with assistance from ChatGPT.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.