James A. Garfield (1831-1881)

Death by Lightning: The Scholar Who Stood Against the Spoilsmen

President’s Day is a fitting moment to return to James A. Garfield—not as a footnote between Hayes and Arthur, but as the gravitational center of one of the most consequential political dramas of the Gilded Age. Last fall’s Netflix series Death by Lightning helped rekindle public interest in Garfield by placing his brief presidency inside a wider constellation of figures—Guiteau, Blaine, Conkling, Sherman—whose rivalries, ambitions, and delusions collided in 1881. What the series makes vivid is that Garfield was not simply “the president who was shot,” but a reformer who wandered into the White House at the precise moment when the spoils system, factional warfare inside the Republican Party, and the unfinished business of Reconstruction were all coming to a breaking point.

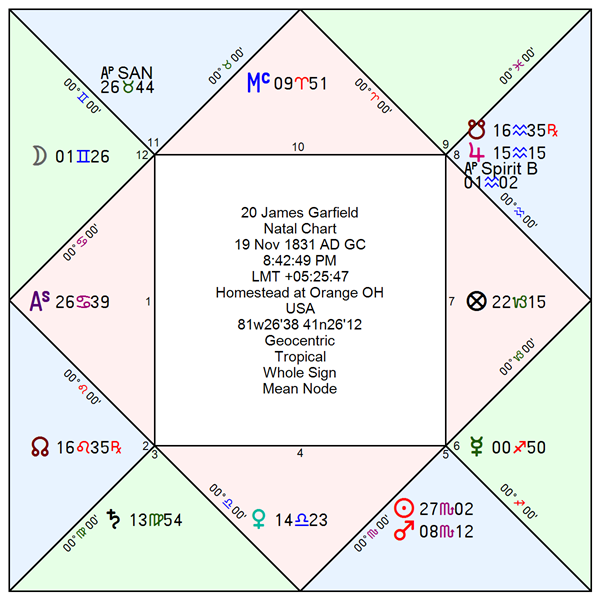

Astrologically, Garfield’s chart mirrors this historical tension. Born just after a Full Moon, with Cancer rising and the Moon in Gemini, his life is shaped by the pressure of visibility and conflict, but lived through the medium of speech, books, letters, and persuasion rather than brute force. The Moon separating from a Scorpio Sun—ruled by Mars in its own sign—describes a man forged in crisis and war, yet temperamentally inclined to translate conflict into argument, administration, and procedural mastery. His nocturnal chart places Mars and Venus in sect: Mars acts effectively but without bloodlust in his Civil War service and later confrontations with party bosses, while Venus in Libra marks him as a compromise figure, the unlikely nominee who emerged from the stalemate between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds in 1880.

This post is part of a larger series examining the “constellation” around Garfield’s presidency—how individual lives, factional politics, and symbolic patterns converged in a single, fatal moment. Garfield’s Moon moves from Mercury through a brief void of course and into Saturn in Virgo: from speech and belief, through political drift, into the grinding labor of budgets, census work, logistics, and airtight argument. That sequence reads like a compressed biography of his public life. On President’s Day, revisiting Garfield through this lens is not an exercise in nostalgia, but a reminder that reform in American politics has often depended on procedural heroes—figures who try to discipline chaos with paperwork, reason, and moral seriousness—and that such figures have historically paid a high price for challenging the machinery of patronage and power.

James A. Garfield rose from canal-boy poverty in northeastern Ohio to become one of the most intellectually formidable politicians of his generation. Largely self-educated, he pursued learning with near-obsessive intensity, mastering Greek, Latin, mathematics, and history, and later served as a teacher and president of Hiram College. Garfield never lost the habits of the struggling scholar. Books were not social ornaments for him but tools of self-formation; he read constantly, annotated deeply, and treated ideas as a moral discipline. This intellectual seriousness gave him an unusual authority in an age when many politicians were celebrated more for factional loyalty than for thought.

Garfield’s rhetorical gifts were central to his rise. He was one of the most powerful public speakers of the post–Civil War Republican Party, capable of sustained argument rather than mere applause lines. In Congress, he could command the floor for hours, weaving moral language, policy detail, and party strategy into a single performance. His speaking style—earnest, logical, and emotionally charged without being theatrical—made him an effective bridge figure between reform-minded Republicans and party pragmatists. This talent for persuasion, more than personal ambition, carried him into national prominence.

During the Civil War, Garfield proved himself not merely courageous but administratively capable. Commissioned as an officer, he became especially valued for logistics, organization, and the management of men and supplies in chaotic frontier commands in Kentucky and Tennessee. His military reputation rested less on battlefield heroics than on competence: stabilizing disordered units, coordinating movements, and bringing bureaucratic coherence to Union operations in difficult terrain. This experience shaped his later politics. Garfield emerged from the war with a technocratic streak—an appreciation for the unglamorous work of administration that makes large systems function.

Returning to Congress, Garfield became a policy workhorse. He developed a reputation for mastering complex, technical legislation—especially matters involving federal finance, representation, and census administration. The census was not glamorous politics, but it was foundational to representation and federal power, and Garfield repeatedly involved himself in its procedural and statistical underpinnings. This blend of moral rhetoric and bureaucratic seriousness placed him squarely in the reformist wing of the party and increasingly at odds with the patronage-driven spoils system that dominated Republican machine politics.

The turning point of Garfield’s national career came at the 1880 Republican National Convention. Garfield arrived not as a presidential candidate but as a manager and advocate for John Sherman, the Ohio senator and treasury secretary whose candidacy represented the reformist “Half-Breed” faction against the Stalwart machine led by Roscoe Conkling and aligned with Ulysses S. Grant’s attempted political comeback. Garfield’s nomination speech for Sherman was a triumph of oratory, and although Sherman failed to break the deadlock between Grant’s Stalwart supporters and James G. Blaine’s Half-Breed faction, Garfield’s performance unexpectedly elevated him as a unifying figure. As the convention stalled through dozens of ballots, the bitter rivalry between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds created an opening for a compromise candidate who was respected by both sides but owned by neither. Garfield, initially resistant and genuinely surprised by the turn of events, emerged as that compromise—an accidental nominee produced by factional exhaustion rather than personal plotting. His rise was a testament to how rhetorical authority and perceived integrity could outweigh raw machine power in moments of party crisis.

Garfield entered the presidency burdened from the start by the realities of 19th-century governance. The White House functioned as a patronage clearinghouse, and office seekers besieged him daily, treating access to appointments as a political right. Managing these demands consumed enormous time and emotional energy and placed him immediately in conflict with the Stalwart faction, which expected control over key appointments—especially in New York’s customs house, the most lucrative patronage prize in the federal government. Garfield’s insistence on asserting presidential authority over appointments was not merely personal; it was a structural challenge to the spoils system itself, one that put him on a collision course with Roscoe Conkling and the Stalwart leadership.

The vulnerability of the presidency in this period is easy to forget. Garfield had no Secret Service protection; the Secret Service existed only as a Treasury unit focused on counterfeiting, not presidential security. Presidents moved with minimal security, met the public freely, and were physically accessible in ways that would later become unthinkable. This openness operated in tandem with a chaotic patronage culture in which office seekers crowded the White House daily, pressing personal claims for government jobs. The combination of minimal security and constant, informal access created an environment in which resentful petitioners could drift in and out of the president’s orbit with little oversight. This lapse in security, layered on top of a chaotic environment of continuous office-seeking, allowed someone like Charles Guiteau—a delusional and embittered seeker of patronage—to get dangerously close to the president.

Guiteau understood politics entirely through the logic of the spoils system. He aligned himself with the Stalwart faction, which openly defended patronage as a system of rewarding loyalty to the party cause with federal employment. In his own mind, Guiteau had “earned” such a reward by writing and circulating a rambling campaign speech in support of Garfield’s election, later convincing himself—delusionally—that this speech had helped secure Garfield’s victory. When he repeatedly petitioned both President Garfield and Secretary of State James G. Blaine for a diplomatic post in Paris and was ignored or rebuffed, Guiteau interpreted the refusals not as the normal functioning of government but as personal betrayal. He concluded that removing Garfield would allow Chester A. Arthur, a Stalwart, to ascend to the presidency—and that under a Stalwart administration, his supposed loyalty would finally be repaid with office. In this warped logic, the assassination became, to Guiteau, a political transaction: the restoration of the patronage system he believed entitled him to reward.

Garfield was shot on July 2, 1881, and lingered for nearly eleven weeks before dying on September 19. The gunshot wound itself was not immediately fatal. Contemporary medical practice, however, proved disastrous. Physicians repeatedly probed the wound with unsterilized fingers and instruments in a desperate effort to locate the bullet, introducing infection and worsening internal damage. The treatment environment ignored the antiseptic methods being advocated in Europe by Joseph Lister, and American medicine had not yet widely adopted germ theory in practice. Modern medical assessments generally agree that Garfield’s death resulted less from the initial wound than from sepsis and complications caused by aggressive, non-sterile intervention. There remains debate about whether Garfield would have survived had the wound been left largely undisturbed, or had antiseptic procedures been used from the outset, but the prevailing view today is that with basic wound sanitation—or by modern standards—Garfield had a strong chance of survival. In this sense, his death stands as both a political and medical tragedy: a survivable injury made fatal by the limits of 19th-century American medicine.

Despite the brevity of his presidency, Garfield had articulated serious ambitions. He favored civil service reform to weaken the spoils system, supported the strengthening of federal authority to protect Black voting rights in the South, and envisioned a more professionalized, merit-based administration. He also showed interest in modernizing the Navy, promoting education, and encouraging economic development through internal improvements. Garfield imagined the presidency not as a mere dispenser of offices but as a moral and administrative center capable of reasserting federal integrity after the long drift of Reconstruction-era corruption and factionalism. His assassination froze that project in mid-gesture, leaving behind the haunting counterfactual of a reform presidency that never had the chance to take shape.

Rodden Rating A: from memory. 2:00 AM, ASC 28VI06

2022 Proposed Rectification: 8:42:49 PM, ASC 26CA39’30”

Rectification Note: Within the Presidential database, my proposed rectification for Garfield differs substantially from the A-rated birth time of 2:00 AM based on Charles Latimer, a close friend of the family given the data by Garfield’s mother and published in 1942. Using Stage I rectification techniques I argue that Mercury must be in Sagittarius (not Scorpio) because Garfield fell into the water over fourteen times during a summer job walking horses on a towpath pulling barge traffic. Likewise the Moon must be in Gemini (not Taurus) because of Garfield’s penchant for reading and collecting books which littered every room of his house. Garfield was also born into poverty and was never a materialist (were the Taurus Moon to be accurate). These two simple observations limit the birth time to between 6:27 PM and 12:00 Midnight for his birthday. Garfield must be born during evening nocturnal hours. Please refer to my book A Rectification Manual: The American Presidency. 4th edition, pps 438-555 for a summary of these observations, directions, and other methods used to fine tune the Ascendant degree.

Complete biographical chronology, rectification and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model Factors favoring Saturn/Virgo

· Sign ruler: Lot of Fortune, Lot of Spirit

· Bound ruler: Ascendant, Sun, Lot of Fortune, Prenatal Syzygy

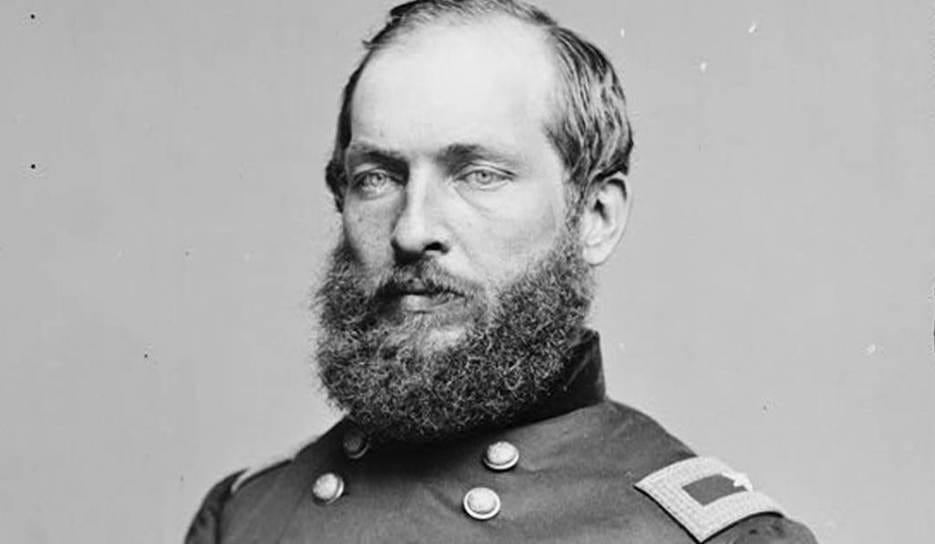

Physiognomy factors favoring Pisces

· Third rising decan of Cancer is Pisces which matches the shape of Garfield’s eyelids.

· In traditional physiognomy, the partially veiled upper eyelid—soft flesh shading the eye rather than leaving it fully exposed—is a classic watery or Piscean marker. Greek and late antique physiognomists (Polemon, Adamantius, Pseudo-Aristotle) associate this eye-type with emotional permeability, inward reflection, compassion, and susceptibility to psychological strain rather than outward aggression. Renaissance writers such as della Porta extend this symbolism by likening such eyes to aquatic creatures: present, receptive, and emotionally porous rather than defended. Medieval astrological physiognomy then maps this eye-type to Pisces in particular, whose natives are described as gentle-eyed, contemplative, and morally sensitive.

· Garfield is a strong delineation match for this configuration: his inward, bookish temperament, moral rumination, and emotional permeability to political pressures fit the watery physiognomic profile more closely than the hardened, aggressive eye-type associated with martial or Saturnine natures. The soft, partially hooded gaze seen in many photographs mirrors a life marked by absorbing strain rather than deflecting it—bearing the psychic weight of factional conflict, patronage demands, and moral responsibility rather than imposing force through sheer political will.

Moon’s Configuration

Phase I — Full Moon separating from the Sun (Scorpio, 5th house)

Delineation. The Moon separating from a Full Moon opposition to the Sun describes a life inaugurated under maximum tension between lunar life conditions and solar authority. The Sun in Scorpio in the 5th house places authority in arenas of performance, public display, persuasion, symbolic leadership, and moral theater. Scorpio’s bound of Saturn hardens this solar expression: authority is constrained by surveillance, suspicion, national-security logic, and the pressure of crisis management rather than free self-expression. The Sun’s sign ruler Mars in Scorpio adds martial gravity: authority arises not from theatricality alone but from confrontation with danger, conflict, and existential threat. This is not the Sun of ease or celebration; it is a Sun forged in crisis, discipline, and combat.

The Moon in Gemini separating from this Sun describes a native whose intellectual life detaches from performative authority. Gemini signifies letters, speeches, books, clerks, reports, rumor, and communication networks. The separating aspect indicates that the native’s emotional and practical life repeatedly moves away from raw authority and crisis toward mediation, explanation, translation, and connective labor. The Full Moon phase intensifies visibility and pressure: the native is formed under conditions where private thought is constantly exposed to public conflict.

Biographical Match. Garfield’s life fits this signature with striking clarity. His solar authority was forged through crisis and war rather than comfort: his participation in the Civil War reflects Mars ruling Scorpio—he did not seek battle, but when battle came to him, he met it directly. The Sun in Saturn’s bound in Scorpio maps well onto his later immersion in matters of scrutiny, discipline, and national security logic during Reconstruction politics. Yet Garfield’s actual mode of operation consistently moved away from raw command toward Gemini mediation: speeches, letters, policy explanation, and intellectual persuasion. He was not a charismatic strongman president-in-waiting but a rhetorician, logician, and explainer-in-chief, forever translating power into argument. His bookish temperament and love of reading reflect the Moon in Gemini separating from martial authority toward the life of the mind.

Phase II — Moon applying to Mercury (Sagittarius, 5th/6th)

Delineation. After separating from the Sun, the Moon immediately applies to Mercury in Sagittarius, a debilitated Mercury in its detriment, placed in the 5th/6th house region. Mercury rules the 12th in this chart, binding the themes of hidden enemies, self-undoing, and confinement to speech, belief, optimism, and misjudgment. Mercury in Sagittarius speaks boldly but imprecisely; it prefers grand narratives over careful details. This creates a structural tension with the Moon in Gemini: meticulous curiosity moving toward inflated rhetoric, ideological speech, and overconfident interpretation. The Moon’s application suggests that life circumstances repeatedly funnel the native’s emotional and practical affairs into environments where speech, belief, and optimism become entangled with hidden enemies, illness, labor, and vulnerability.

Biographical Match. This configuration is uncannily literal in Garfield’s life. Moon in Gemini signifies letters and speeches; Guiteau’s fixation on the speech he carried around—believing it helped elect Garfield—belongs squarely to this Mercury/Sagittarius distortion of reality. Mercury ruling the 12th ties speech to hidden enemies: Guiteau, the secret enemy, emerges from the realm of delusional rhetoric and ideological entitlement. Mercury in the 6th also describes medical professionals and treatment environments. At the end of Garfield’s life, it was the overconfident, misguided medical intervention—optimistic probing, faith in technique without antisepsis—that contributed to his death. The same Mercury/Sagittarius signature appears earlier in Garfield’s biography in lighter form: the famous fourteen falls into the canal during his youth can be read as Mercury ruling the 12th—misjudgment, distraction, bodily mishaps—under a Sagittarian optimism that overestimates one’s footing.

Phase III — Void of Course, Application to Saturn (Virgo, 3rd)

Delineation. The Moon’s brief Void of Course before applying to Saturn is structurally crucial. In traditional doctrine, the VOC Moon signifies a period in which actions fail to connect to stable outcomes—motion without traction, effort without resolution. Emerging from Mercury’s overconfident speech into a VOC interval, the life temporarily enters zones of drift, exhaustion, or misalignment. The subsequent application to Saturn in Virgo on the 3rd cusp reimposes structure through discipline of detail, accounting, measurement, and bureaucratic scrutiny. Saturn in Virgo is the master of budgets, census data, logistics, classification systems, and procedural rigor; on the 3rd cusp, it governs documents, correspondence, clerks, and administrative infrastructure. This is the configuration of power through paperwork.

Biographical Match. Garfield’s biography follows this rhythm precisely. Periods of political drift and frustration—especially amid the chaos of patronage politics and ideological speech—are repeatedly followed by his retreat into Saturn/Virgo competence: census administration, budgetary oversight, logistics during the Civil War, and procedural mastery in Congress. The Moon’s movement from Mercury (speech, belief) through VOC (political paralysis) into Saturn (discipline, detail) describes how Garfield repeatedly reasserted control not through charisma but through airtight logic, documentation, and mastery of technical detail. This is the engine of his speaking style: he destroyed opponents not with flourish but with procedural exactitude, forensic argument, and the ability to translate bureaucratic minutiae into moral persuasion.

Phase IV — Moon trine Venus (Libra, 4th)

Delineation. After Saturn imposes discipline, the Moon’s trine to Venus in Libra near the 4th cusp introduces the harmonizing function: diplomacy, balance, courtesy, and factional negotiation within the domestic and foundational structures of life. Venus in Libra excels at smoothing conflicts, mediating between rivals, and restoring equilibrium. This trine suggests that after the hard labor of Saturnian administration, life seeks reconciliation, alliance-building, and the softening of conflict within the political “house.”

Biographical Match. Garfield’s role as a conciliator between factions—especially between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds—fits this phase. His temperament was not that of a factional warrior but of a negotiator seeking balance and institutional harmony. Even his accidental nomination at the 1880 convention reflects this Venusian function: he became the candidate precisely because he could restore equilibrium after factional deadlock. In personal life, this Venus phase also reflects his attachment to domestic stability and emotional anchoring after periods of political strain.

Phase V — Moon trine Jupiter (Aquarius, 8th)

Delineation. The final application to Jupiter in Aquarius in the 8th universalizes the narrative. Jupiter in Aquarius signifies humanitarian ideals, collective welfare, and reformist visions oriented toward the future of the polity. Placed in the 8th, it carries themes of death, legacy, and the transformation of public institutions through loss. The trine indicates that the native’s life culminates in a meaning that transcends personal survival, embedding reformist ideals into collective memory through sacrifice.

Biographical Match. Garfield’s humanitarian commitments—to civil service reform, to federal responsibility for Black citizenship rights, and to meritocratic governance—fit Jupiter in Aquarius precisely. The 8th-house placement literalizes the outcome: his death becomes the catalyst for civil service reform, transmuting personal tragedy into institutional transformation. In this sense, Garfield’s life completes the configuration’s arc: from speech and misjudgment, through administrative discipline and diplomatic balance, into a reformist legacy sealed by death.

Interpretive Summary

The spine of Garfield’s Moon configuration is the movement from Mercury (speech, belief, misjudgment) through Void of Course (political paralysis, drift, vulnerability) into Saturn (procedural mastery, bureaucratic discipline). This is the lived pattern of his career: rhetoric entangled with illusion and enemies, periods of institutional chaos, and repeated recourse to Saturnine competence—logistics, census work, budgets, documentation—as the means of restoring order. The Sun in Scorpio, ruled by Mars in Scorpio, supplies the background of crisis and conflict; the Moon in Gemini supplies the intellectual engine; Saturn in Virgo supplies the method by which crisis is actually managed. Venus and Jupiter then shape the moral outcome: diplomacy first, reformist legacy through death.

This is not the chart of a charismatic conqueror. It is the chart of a procedural hero: a man whose power lay in translating crisis into paperwork, speech into structure, and conflict into institutional reform—at the cost of personal safety in a world that had not yet learned how to protect its reformers.

Influence of Sect

Garfield’s nocturnal sect clarifies why Mars and Venus function constructively while Jupiter and Saturn operate against the grain of his era. Mars in Scorpio, in sect, acts with disciplined effectiveness rather than partisan fury: Garfield did not seek combat in the Civil War, but when conflict came to him he met it directly and competently, and the same restrained martial posture appears later in his political life in his willingness to confront figures like Conkling without becoming a factional brawler. Venus in Libra, also in sect, helps explain his emergence as a compromise candidate in 1880 and his instinct to balance rival factions through courtesy and negotiation rather than machine politics. By contrast, Jupiter in Aquarius out of sect places Garfield’s humanitarian and egalitarian vision out of step with the political climate that followed the 1876 election of Rutherford B. Hayes, when Reconstruction collapsed into the early Jim Crow backlash; his universalist ideals were structurally misaligned with the national mood, leaving his reform vision morally coherent but politically isolated. Saturn in Virgo out of sect does not so much cripple Garfield as burden him: the Saturnian labors of census administration, debt analysis, logistics, and procedural mastery fell heavily upon him and required sustained, exhausting effort rather than flowing naturally from circumstance. Biographically, this shows up in the sheer grind of his legislative life—long hours of technical preparation, forensic debate, and administrative detail-work—by which he earned authority through labor rather than inheritance of power, a Saturnian load made heavier by its out-of-sect condition.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

James A. Garfield makes for a tricky test case for the early/late bloomer thesis. Born just after a Full Moon, he falls on the waning side of the lunar cycle, which would ordinarily predict a “late bloomer” pattern, with major authority and fulfillment arriving after the midpoint of life. But Full Moon births tend to blur this model: they often produce early visibility and early responsibility alongside later culmination or strain, rather than a clean delay in development. In Garfield’s case, the life midpoint (mid-1850s) arrives after he has already completed his education, become a college president, entered national politics, and begun building the reputation that would carry him through the Civil War and into Congress.

At the same time, Garfield’s ultimate symbolic culmination—the presidency—does come very late, at age forty-nine, only months before his death. This makes him look like a “late bloomer” in outcome but not in formation: the groundwork for his authority was laid early, even if the final office arrived at the end. Taken together, Garfield neither clearly confirms nor cleanly contradicts the early/late bloomer model. Instead, he illustrates one of its limits: New Moon and Full Moon births often resist simple classification, producing lives with both early prominence and late culmination, which weakens the model’s predictive clarity in cases like his.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.