This post continues the series on the constellation of figures surrounding President James A. Garfield’s rise and fall, and it begins, fittingly, at the dramatic hinge point dramatized in Death by Lightning: the Republican convention of 1880, where three men stood as rival embodiments of the party’s future—Ulysses S. Grant, John Sherman, and James G. Blaine. Grant was the candidate of the Stalwarts, the faction that believed in iron party discipline, patronage control, and the spoils system as the glue of Republican power; a “stalwart” was not a moral label but a partisan one, denoting loyalty to the machine and to the right of party bosses (especially Roscoe Conkling) to control appointments and rewards. Blaine (along with Sherman) belonged to the opposing Half-Breed tendency—a slur that came to mean Republicans who wanted to break the Stalwarts’ grip on patronage and party machinery, while remaining fully committed to the Gilded Age political economy of railroads, tariffs, and national development. The split was not between clean politics and dirty politics so much as between two kinds of corruption: the Stalwarts’ spoils-and-patronage machine, anchored in customs-house revenues and officeholding, versus the Half-Breeds’ legislative–corporate entanglement with railroads, bonds, and promotion.

Blaine himself embodied this ambiguity. Just four years earlier, in 1876, he had been denied the nomination under the cloud of corruption charges typical of the era; yet he survived because his power base was national rather than provincial, his charisma and oratorical skill kept delegates loyal, and his rivals were themselves compromised in the public mind. By 1880 he remained standing and intent on breaking the Grant–Conkling machine, ultimately releasing his delegates to Garfield when the convention deadlocked—a decisive act that made Garfield president—while Conkling, true to Stalwart form, refused to release Grant’s. This places Blaine at the fulcrum of Garfield’s story: indispensable to Garfield’s ascent, then central to the administration as Secretary of State, yet himself repeatedly unable to push past the final threshold of the presidency in 1876, 1880, and again in 1884.

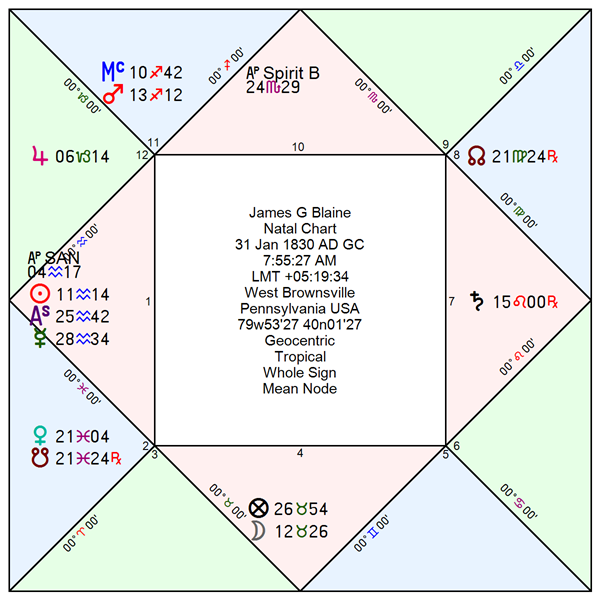

The astrology sharpens the paradox: Blaine’s Moon and Mercury in their respective houses of joy mark him as a gifted public speaker who reads the crowd and commands attention, while his configurations with Saturn describe the recurring pattern of confrontation with entrenched authority that hardens his style and blunts his appeal at the decisive moment. Like Sherman, he is a consummate political instrument who cannot quite cross the finish line; the chart describes a man made to shape events from the center of power, even when the ultimate prize remains just out of reach.

James Gillespie Blaine (1830–1893) was the most formidable party leader of the late Reconstruction and early Gilded Age Republican Party—a figure who came to personify both the party’s national ambitions and its moral ambiguities. Rising from newspaper editor and Maine state politician to Speaker of the U.S. House (1869–1875) and later Secretary of State under James A. Garfield and Benjamin Harrison, Blaine stood at the center of Republican power during the party’s transition from a moral crusade against slavery into a vehicle for industrial expansion, railroad capitalism, and American commercial nationalism. For nearly three decades, he was a perennial presidential contender and the chief rival to the party’s Stalwart faction, led by Roscoe Conkling, whose power rested on rigid party discipline and the patronage machinery of New York’s customs house. The Blaine–Conkling feud defined Republican politics in the 1870s and early 1880s and fractured the party into two competing styles of rule: Blaine’s fluid, coalition-driven “Half-Breed” leadership versus Conkling’s centralized, patronage-based machine.

Blaine styled himself as a reformer against machine politics. He championed the authority of the executive over senatorial control of appointments, spoke the language of civil service reform, and cultivated reformist allies within the party. Yet his reformism was never a wholesale rejection of transactional politics; it was a rejection of Conkling’s control over the transactions. Where Conkling enforced loyalty through a formal spoils system, Blaine assembled power through newspapers, convention maneuvering, delegate networks, and personal alliances with financiers and railroad promoters. The distinction was real—Blaine lacked Conkling’s rent-producing patronage empire—but the overlap was also real: both men practiced factional discipline, treated politics as a system of rewards and obligations, and personalized power around themselves. To contemporaries and critics, the feud often looked less like reform versus corruption than like two rival machines fighting over who would run the party.

This moral ambiguity came to a head in the scandals that shadowed Blaine’s career, especially the Mulligan letters affair of 1876, which revealed his entanglements with railroad interests. Though never convicted of wrongdoing, Blaine became a national symbol of the Gilded Age’s blurred boundary between public office and private enrichment. His response—procedural maneuvering, emotional appeals, and partisan framing of investigations—mirrored the tactical politics he condemned in the Stalwarts, reinforcing the perception that the party’s internal war was corruption confronting corruption rather than reform confronting abuse. That perception proved politically devastating. Reform Republicans (the Mugwumps) bolted in 1884, endorsing Democrat Grover Cleveland over Blaine on grounds of personal integrity, and their defection helped cost Blaine the presidency in one of the closest elections in American history.

Blaine’s later career as Secretary of State showcased the constructive side of his ambition: he articulated an expansive, commercial nationalism that sought to project American power into the Western Hemisphere and the Pacific, foreshadowing the United States’ later emergence as a hemispheric and imperial power. Yet even here, the party he helped shape bore the scars of his factional style. By the 1880s, Democrats increasingly framed national politics as a choice between corruption and corruption—Republican machines versus Republican financiers—casting themselves as the party of probity by contrast. Blaine’s personal story thus became inseparable from the Republican Party’s reputational decline in that decade: he embodied its dynamism, its organizational genius, and its outward-looking nationalism, but also its internal civil war, its transactional habits, and the erosion of moral credibility that made reformers defect and voters receptive to Democratic attacks.

No Astrodatabank Record

Proposed rectification: 7:55:27 AM, ASC 25AQ42’25”

Needs further documentation but extremely comfortable with rising decan, and LOF/LOS sign placements

Complete biographical chronology, rectification and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model Factors favoring Saturn/Leo-retrograde as the Victor

· Sign ruler of the Sun, Ascendant, and Prenatal Syzygy

· Bound ruler of Lot of Fortune, Ascendant, Prenatal Syzygy

· Arcronycal Rising

· Angular in 7th house

Physiognomy Model Factors favoring Venus/Pisces

· Rising decan is Libra ruled by Venus/Pisces. Yields round facial shape framed by beard.

· Partile conjunct with South Node limits the amount of flesh that Pisces normally contributes to the face.

Moon’s Configuration

Phase I – Moon separating from the Sun (Aquarius, 12th QS / 1st WS)

Delineation. The Moon separating from the Sun in Aquarius situates Blaine’s public persona at a point of emergence from obscurity into visibility, with the luminary in the bound of Venus lending a conciliatory, beneficent tone to authority. This is not a hostile Sun; rather, it is a Sun disposed to cooperation, public works, and the extension of collective benefit through institutions. The Sun’s placement in Aquarius emphasizes organized social projects, national coordination, and the improvement of civic infrastructure, while its bound by Venus and the presence of Venus in Pisces (despite her diminution by the South Node) incline authority toward ideals of generosity, amelioration, and the public good. The Moon in Taurus in the place of her joy, in Mercury’s bound and in close configurational sympathy with Mercury rising near the Ascendant and his own place of joy, frames the emotional and rhetorical engine of the nativity: the native becomes legible to the public as a persuasive voice who can translate abstract civic ideals into accessible speech. This is a configuration that recognizes the legitimacy of large-scale public works, national development, and institutional action as vehicles for distributing material benefit across the populace, and it explains Blaine’s instinctive alignment with projects of national expansion, railroads, and commercial integration as civic goods, not merely private gain.

The t-square formed by Mercury, Sun, Moon, and Saturn establishes the core tension of the nativity: public speech and visibility are structurally linked to conflict with authority, resistance, and constraint. Even before the Moon applies to Saturn, the separating phase from the Sun shows the native moving away from a broadly inclusive, beneficent vision of authority toward a more combative field of action. The Moon’s joy in Taurus gives durability and popular receptivity to his speech; Mercury near the Ascendant amplifies this into a highly effective public presence. But the geometry of the configuration already prefigures that the exercise of this public voice will provoke opposition from entrenched authorities, and that the transition from benevolent civic vision (Sun/Venus) to hardened political contest (Saturn) is structurally unavoidable in the life.

Biographical match. Blaine’s early national rise fits this separating phase with striking clarity. His emergence as a dominant congressional speaker and organizer is accompanied by rhetoric and policy positions that frame national development—railroads, internal improvements, protective tariffs, and later Pan-American commercial integration—as vehicles for spreading prosperity and binding the country together after the Civil War. He consistently cast large-scale public works and state-supported development not as narrow class enrichment but as instruments of national benefit. This is precisely the Sun-in-Aquarius logic in Venus’s bound: authority justified through collective improvement and the visible distribution of material benefit. His public reputation in the late 1860s and early 1870s rests on this synthesis of eloquence and developmental nationalism, and contemporaries recognized him as a politician who could articulate national purpose in language that resonated with a wide audience.

At the same time, the structural tension of the t-square is already operative. Blaine’s ascent is accompanied by growing resistance from established power centers, especially the Stalwart machine. Even as he advances projects framed as public goods, he becomes entangled with the financial and institutional mechanisms required to execute them. The same configuration that gives him popular speech and a credible civic vision places him in the crossfire between idealized public benefit and the realities of power-brokering. This is why his developmental nationalism never remains purely rhetorical; it immediately draws him into contests over who controls the machinery of distribution—appropriations, railroads, patronage, and party organization—setting the stage for the Saturnian phase that follows.

Phase II – Moon applying to Saturn (Leo retrograde, 6th QS / 7th WS; acronychal rising)

Delineation. The Moon’s application to Saturn retrograde in Leo brings the public and emotional field into direct confrontation with authority exercised through domination, hierarchy, and personal command. Although retrograde Saturn often behaves as if inverted in sign, the acronychal rising condition overrides this general rule: Saturn here is at his brightest and most forceful, operating with maximal visibility and confrontational presence. The square from Taurus to Leo describes a tension between popular goodwill and durable public support (Moon in joy) and the coercive assertion of authority through spectacle, rank, and personal dominance (Saturn in Leo). This is not quiet obstruction; it is public conflict with powerful figures who command loyalty and enforce discipline. The Moon’s application indicates that the native’s public reception and emotional life become increasingly shaped by these confrontations, and that the exercise of authority will require adopting harder methods than the earlier Venusian Sun would prefer.

Because Saturn occupies the 7th by whole sign, the primary theater of this conflict is open rivalry with political enemies. The application signifies that the native is drawn into contests of will, reputation, and supremacy with adversaries who embody entrenched authority. The acronychal brightness of Saturn intensifies the visibility of these struggles and makes compromise difficult. This is where the nativity departs from pure reformist posture: the Moon, as the significator of public connection, is compelled to meet Saturn on Saturn’s terms. The result is a mode of operation that can resemble the very authoritarian tactics the native opposes, not because the native embraces those values in principle, but because the configuration requires confronting visible, dominant authority with methods capable of matching its force.

Biographical match. Blaine’s public conflicts with Roscoe Conkling and the Stalwarts exemplify this application to Saturn in Leo at acronychal rising. Conkling embodied Saturn-in-Leo authority: rigid hierarchy, personal command, and the theatrical display of power rooted in institutional control. Blaine’s struggle with this machine was not conducted through quiet reform alone; it increasingly took the form of open, confrontational political combat—contests over appointments, conventions, and public legitimacy. In practice, Blaine often met Conkling’s Saturnian methods with Saturnian methods of his own: factional discipline, strategic pressure, and the assertion of personal authority within the party. This is precisely the Moon’s square to a bright, confrontational Saturn: the native’s public standing becomes entangled with strong-arm political dealings that puzzle observers who expect a purely reformist style.

This Saturnian application also explains the reputational cost of Blaine’s fame. His popular eloquence and developmental nationalism (Phase I) generate wide support, but the subsequent confrontations with entrenched authority harden his style and erode the moral clarity of his position. To many observers, the conflict begins to look like power confronting power rather than reform confronting abuse. This is where Blaine’s public reception becomes divided: admired as a national tribune and organizer of public works and commercial nationalism, yet criticized for employing tactics that mirror those of his enemies. The Moon’s application to Saturn thus describes the squandering or narrowing of goodwill you noted: the same fame that arises from persuasive public speech is partially consumed by visible, acrimonious struggles with dominant rivals, leaving his public image marked by conflict and ambiguity rather than unambiguous reform.

Influence of sect

The figure is diurnal, which tempers Saturn’s maleficence and makes his opposition more legible and politically survivable rather than purely destructive; Saturn’s harms tend to manifest as durable constraints, entrenched rivals, and long contests for authority rather than immediate ruin. By contrast, Jupiter in Capricorn in the 11th by quadrant (12th by whole sign) is a corrupt placement that implicates Blaine in illicit or compromising associations with powerful networks—most notably railroad and finance interests—yet as the in-sect benefic this corruption is normalized within the political culture of the period: many others operate the same way, so the placement does not in itself disqualify him from high office. Instead, it functions as reputational baggage that accumulates over time and becomes electorally salient when contrasted with a cleaner opponent; this logic fits the 1884 election, where Cleveland’s reformist profile without the same taint sharpens Blaine’s vulnerability. Both Venus and Mars are out of sect, which constrains beneficence and roughens the execution of ambition; in particular, Mars in Sagittarius conjoined the Midheaven describes a career conducted through aggressive public assertion, crusading rhetoric, and high-visibility confrontation. While this does not require literal physical violence, the historical record supports recurrent political blowups and acrimonious episodes (floor confrontations, convention brinkmanship, factional warfare) as a defining feature of Blaine’s public life; accordingly, Mars out of sect at the 10th promises a career repeatedly marred by contentious outbursts and reputational scorch marks rather than steady, untroubled ascent.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

James G. Blaine tests as a hybrid against the early/late-bloomer thesis: born just after a New Moon, he shows an unmistakable early-bloomer signature in the speed of ascent, capturing real institutional leverage before his midpoint (30-Jul-1861) through his rapid rise from journalism into state power and the speakership of the Maine House by 1861–62, which establishes the career trajectory that never reverses. Yet the offices and crises that define his historical magnitude—Speaker of the U.S. House (1869–1875), U.S. Senator, Secretary of State, the Mulligan letters stigma, and the 1884 presidential nomination and defeat—are concentrated after the midpoint, indicating that while the arc of authority is set early, the weight of consequence, reputation, and legacy accrues later; the figure therefore fits the thesis in tempo but not in culmination, producing a mixed outcome in which early rise coexists with later defining outcomes.

AI Notice: This post created with assistance from ChatGPT.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.