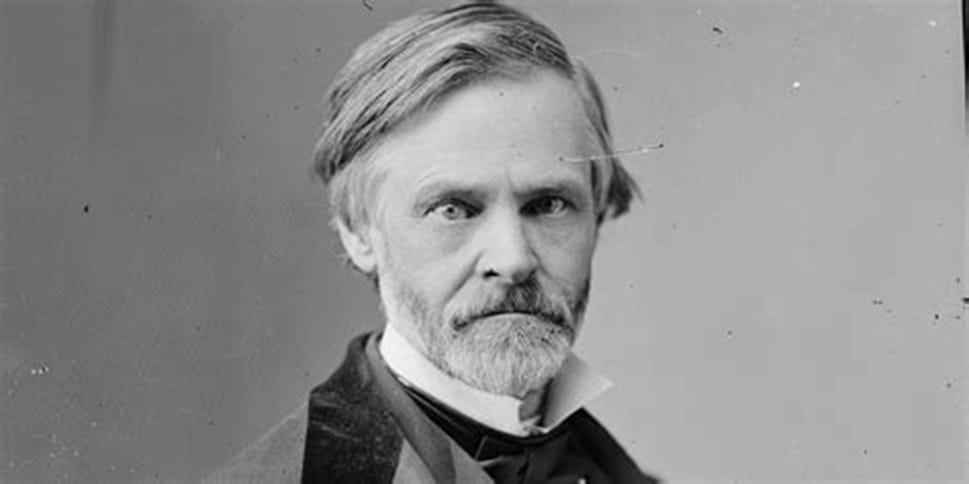

John Sherman (1823 – 1900)

Death by Lightning: The Man who Launched the Garfield Presidency

As we approach Presidents’ Day next Monday, John Sherman is the next horoscope to fill out the constellation of men surrounding the rise and fall of President James A. Garfield. In the Netflix series Death by Lightning, Sherman barely registers—a fleeting background figure in the Republican machine. In reality, he stood at the center of the drama that produced Garfield’s presidency. It was Garfield’s nomination of Sherman for the Republican presidential ticket on 5 June 1880 that set the convention’s machinery in motion; when delegates failed to secure the nomination for Ulysses S. Grant, James G. Blaine, or Sherman himself, the deadlock opened the door to Garfield’s emergence as the dark-horse compromise. By 1880, Sherman had earned his place at the top tier of Republican power through decades of legislative leadership—war finance, national banking, currency stabilization, and, most recently, the successful execution of the Resumption Act, which restored greenbacks to gold parity in 1879. For contemporaries, Sherman was not a bit player but one of the party’s principal architects of modern fiscal governance.

Astrologically, Sherman’s chart explains both his reach and his ceiling. With Leo rising and the Sun in the 10th house, he enjoys sustained public rank and access to the highest offices of the state; his Moon’s application to a Gemini stellium in the 11th house, with Jupiter in sect as victor, describes a career built on committees, rules, and institutional networks that expand the scope of federal power through law. This is the chart of a master legislator: durable influence, technical command, and the ability to scale policy to the national level. Yet Sherman is born under a New Moon with the Moon combust, a configuration that places him close to authority while limiting the specifically lunar talent for unifying rival factions behind himself. He becomes indispensable to the machinery of power without becoming the singular figure who commands it by personal magnetism. The astrology fits a man whose authority grows with institutions, not with charisma.

This tension helps explain why Garfield’s objective at the 1880 Republican National Convention was to nominate Sherman for president. Garfield entered the convention as Sherman’s campaign manager and floor general, believing that Sherman’s legislative stature, financial achievements, and standing within the party’s governing elite made him the natural choice to unify the Republicans after Ulysses S. Grant’s third-term bid stalled. The effort failed not because Sherman lacked accomplishments, but because his coalition could not be welded into a final majority; the deadlock instead elevated Garfield himself as the compromise nominee. The chart tells the story in advance: John Sherman is built to expand and stabilize the system, not to personify it.

John Sherman was one of the central architects of Republican economic policy in the second half of the 19th century, a career statesman whose influence on American finance and party organization far outlasted any single administration. Born in Ohio in 1823 into a politically connected family (his younger brother was Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman), John Sherman rose through Congress as a meticulous committee man and institutional operator rather than a charismatic tribune. His temperament was legalistic, procedural, and doctrinal: he believed politics should be conducted through durable policy frameworks, fiscal discipline, and party machinery, not personal rule or theatrical leadership.

Sherman made his name as a financial conservative of the post–Civil War Republican Party, closely identified with hard money, credit stabilization, and the restoration of confidence in federal finance. As a long-serving senator from Ohio and later as Secretary of the Treasury under Rutherford B. Hayes, he became the public face of the Resumption Act of 1875, which returned the United States to specie payments in 1879. This policy cemented his reputation among business interests and eastern financiers as a guardian of monetary stability, even as it alienated inflationists and agrarian reformers who saw resumption as favoring creditors over debtors. Sherman’s politics thus aligned him with the party’s institutional core: banking, railroads, corporate capital, and the administrative state that serviced them.

By 1880, Sherman had become the preferred candidate of a substantial bloc of Republicans at the national convention. He represented continuity with the Hayes administration’s reformist posture and a fiscally orthodox Republicanism that could reassure markets while navigating factional party politics. James A. Garfield’s famous nominating speech for Sherman at the Republican National Convention was intended to present him as a unifying figure capable of bridging the party’s internal divisions. The irony, of course, is that the speech elevated Garfield himself into contention, ultimately producing Garfield as the compromise nominee when the convention deadlocked between factions. Sherman thus occupies a pivotal historical position: the intended standard-bearer whose failure to secure the nomination created the opening through which Garfield rose.

Although Sherman never achieved the presidency, his policy legacy proved enduring. Returning to the Senate after 1881, he became the principal sponsor of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the first major federal attempt to restrain corporate monopolies and combinations. The act was loosely drafted and unevenly enforced in its early years, but its passage placed Sherman’s name permanently at the center of American debates over the limits of corporate power and the role of the federal government in regulating markets. He later served as Secretary of State under President William McKinley, a role in which his age and health limited his effectiveness, but which symbolically capped a career devoted to institutional governance rather than personal ambition.

In the orbit of James Garfield, John Sherman represents the institutional Republican ideal of the era: policy over personality, fiscal orthodoxy over populist appeal, and committee power over executive charisma. His failure to capture the 1880 nomination is therefore instructive. The party did not reject Sherman’s policies; it rejected his inability to command the convention at a moment of factional crisis. Garfield’s rise from nominator to nominee marks the pivot from Sherman’s administrative Republicanism to a more contingent, personality-driven resolution of party deadlock—an outcome that would shape the tragic trajectory of Garfield’s presidency and the volatile political ecosystem that surrounded it.

No Astrodatabank Record

Proposed Rectification: 12:04:55 PM, ASC 27LE17’00”

Complete biographical chronology, rectification and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model Factors favoring Jupiter as Victor

While Venus rules the Sun, Moon, MC, and prenatal syzygy; Jupiter rules the bounds of those same four points. Jupiter/Gemini is the victor.

Physigonomy Model Factors favoring Aries

Ascendant degress is in the third decan of Leo assigned to Aries.

Shape of head is an arrowhead, match to the bony ovate in Willner’s model.

Straight thin lips is another Aries trait.

Moon’s Configuration

Phase I — The New Moon and Combustion (Taurus; Sun in the 10th with Moon)

Delineation. John Sherman is born under a New Moon with the Moon barely past conjunction and still combust. In traditional terms this is a major lunar debility: the Moon’s capacity to act independently in public life is weakened by excessive proximity to solar authority. The result is not obscurity but closeness to power. This configuration places the native near the center of authority and decision-making while limiting the specifically lunar talent for drawing rival factions into personal loyalty. The Moon’s political function is subordinated to the Sun’s executive principle, producing a figure who serves and sustains power more readily than he commands it in his own name. With the Sun (ruler of the Ascendant) in the 10th house, the configuration nonetheless confers enduring public rank, institutional legitimacy, and access to high office throughout life.

Biographical match. Sherman’s career fits this pattern with unusual clarity. He spent decades at the apex of American political institutions—House, Senate, Treasury, and State—yet repeatedly failed to unify disparate factions behind himself as the singular choice for the presidency. The 1880 convention dramatizes this limit: Sherman commands respect, delegates, and organizational strength, but cannot consolidate the final coalition, while a compromise figure emerges from the deadlock. At the same time, his social standing remains high and stable across administrations. He is always close to the throne; he is never the throne.

Phase II — Prenatal Conjunctions with Mars and Saturn (Taurus)

Delineation. Before forming the New Moon with the Sun, the Moon first conjoins Mars and Saturn in Taurus. This sequence imprints conflict and constraint upon the lunar field before identity is fused to authority. In Taurus, these malefics signify pressure, scarcity, and danger around material security: resources, property, credit, and the capacity to fund collective life. Mars introduces contention over money and provisioning; Saturn imposes limits, austerity, and the long weight of obligation. The Sun–Moon conjunction that follows binds the native’s identity to the task of managing these pressures rather than escaping them. The chart thus frames public life as a problem of financing stability under stress, not as a theater of personal triumph.

Biographical match. Sherman’s defining historical role is precisely the management of national financial constraint. He comes of age politically as the federal government confronts existential funding crises, and he becomes a central architect of war finance, currency expansion, banking structure, and postwar stabilization. The burdens of credit, debt, and provisioning are not peripheral to his career; they are its substance. He inherits the malefic pressure around money and translates it into policy architecture. His work consistently addresses scarcity and risk through discipline and structure rather than through spectacle or populist promise.

Phase III — Moon separating from the Sun, still combust (Taurus; bound of Jupiter in Gemini)

Delineation. At birth the Moon separates from the Sun but remains combust, indicating a movement away from solar authority that never fully escapes its glare. Public agency begins to differentiate, yet it remains shaped by proximity to power. The separation occurs in the bound of Jupiter in Gemini, giving the first outward motion of the life a Jupiterian logic of expansion, capacity-building, and enlargement of collective means—channeled through Gemini’s instruments: law, contracts, notes, and administrative intelligence. Authority expands not by decree alone but by proliferating mechanisms of exchange and obligation. The configuration describes the growth of state capacity through legal and financial instruments that radiate outward from the center.

Biographical match. Sherman’s career marks the institutionalization of emergency finance into durable systems. The expansion of the federal monetary apparatus during the Civil War—paper currency, banking frameworks, and the normalization of credit instruments—bears his imprint. He separates from the executive principle not by opposing it, but by converting its demands into scalable mechanisms: statutes, committees, regulatory structures, and financial architecture. The Moon’s Jupiterian bound describes how his public life expands the scope of federal capacity without collapsing the system into disorder.

Phase IV — Sign change (Taurus → Gemini)

Delineation. The Moon’s sign change from Taurus to Gemini is a decisive pivot from substance to mechanism. Taurus is money as thing—bullion, reserves, property, and material stability. Gemini is money as instrument—notes, contracts, circulation, accounting, and legislative language. This shift describes a life that moves from confronting the weight of resources to mastering the intelligence of systems. Problems of value are no longer solved by hoarding substance but by designing frameworks that allow circulation and exchange to function under strain.

Biographical match. Sherman’s genius lies not in controlling wealth as a substance but in building the mechanisms that allow wealth to circulate and stabilize a national economy. His legacy is legislative and administrative: currency systems, banking law, committee governance, and regulatory frameworks. He is a designer of financial plumbing rather than a tribune of material redistribution. The sign change mirrors his movement from the raw problem of funding war to the technical work of creating durable monetary and banking institutions.

Phase V — Moon applying to Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus in Gemini (11th house)

Delineation. The Moon’s application to a Gemini stellium in the 11th house shows public life culminating in institutional networks, legislative coalitions, and the governance of collective resources. Mercury in domicile confers mastery of rules, statutes, and procedural intelligence; Jupiter expands the scale of these systems to the national level and links them to debt and credit; Venus supplies the cohesion required to make complex policy workable within political alliances. The Moon leaves malefics behind and applies to benefics, describing a life trajectory that converts constraint into workable order. The 11th house emphasizes the king’s money, public finance, and the committees and caucuses through which it is administered.

Biographical match. Sherman’s greatest achievements are institutional rather than charismatic: war finance architecture, national banking and currency frameworks, and the later antitrust regime. His work expands the federal money supply and regularizes its circulation in ways that produce inflation without collapse and emergency without systemic ruin. The application to Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus in Gemini describes precisely this outcome: technical design scaled to national capacity and made politically viable through committee politics. In this configuration, Jupiter emerges as victor—the enlargement of state capacity through law and institution, rather than conquest by personal authority, is the governing theme of his life.

Influence of Sect

Because John Sherman’s horoscope is diurnal, Jupiter is the in-sect benefic, and this fact decisively amplifies the meaning of the Moon’s application to the Gemini stellium in the 11th house. The Moon does not merely move toward intelligence, procedure, and committee work (Mercury in Gemini); it moves toward institutional scale and political reach (Jupiter in Gemini) that is fully supported by sect. This is why Sherman’s technical competence does not remain confined to back-room expertise or minor legislative craft. His work in rules, statutes, and financial mechanisms acquires national scope and durability. Jupiter in sect carries Mercury’s technical intelligence into the realm of binding policy and lasting institutional architecture.

In practical terms, this is the chart of a man whose influence grows as the system grows. The Moon’s application to Jupiter in Gemini describes the enlargement of federal capacity through law: war finance becomes national banking; emergency currency becomes durable monetary infrastructure; committee expertise becomes the architecture of the modern fiscal state. Sect makes this expansion legitimate and widely operative. Sherman’s power is therefore not personal or charismatic; it is systemic, increasing as institutions expand, and enduring precisely because Jupiter in sect gives his legislative intelligence the authority to shape the rules by which the system itself operates.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

Tested against the early/late-bloomer thesis, John Sherman offers a qualified match at best—and arguably a failure of the model in its strong form, which is consistent with what this study keeps finding for New and Full Moon births. Sherman lived 77 years (1823–1900), placing the midpoint of his life in 1861. As someone born just after a New Moon, the model would predict an early bloomer—major life themes and peak achievements concentrated in the first half of life. The “early” component is present in a limited sense: by 1861 Sherman had already served multiple terms in the House and was emerging as a national figure as the Civil War opened. But the achievements that define his historical reputation cluster decisively after the midpoint: leadership in war finance and the national banking framework during the war years, long tenure as a Senate power broker, the Resumption Act of 1875, Treasury under Hayes, and the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. Rather than peaking early, Sherman’s career consolidates and matures after midlife, reinforcing the pattern that near-New and near-Full Moon charts tend to blur the early/late signal and produce long arcs of institutional power across the middle decades of life.

AI Notice: This post created with assistance from ChatGPT.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.