Next up in our Jupiter-in-Cancer retrograde series is Sharon Tate. In a diurnal chart, Jupiter in Cancer in the 1st house might ordinarily suggest moral authority, philosophical stature, or a public role shaped by protective wisdom—qualities we see in figures such as Hannah Arendt. Tate’s Jupiter, however, is retrograde. Functionally, it behaves as though placed in Capricorn. Rather than producing a public moral voice, it redirects growth toward worldly ascent: ambition, projection, and advancement through alliance. In Tate’s life, Jupiter does not speak in essays or manifestos. It operates through managers, contracts, and marriage. Martin Ransohoff’s deliberate grooming and Roman Polanski’s artistic sponsorship become the vehicles of her rise. Her career expands not through self-authorship but through those who recognize, shape, and amplify her.

This configuration gives Tate a distinctly relational path to visibility. Jupiter-in-Cancer-retrograde in the 1st does not crown her a thinker or cultural authority; it makes her projectable. Others see possibility in her and move her forward. She becomes a luminous surface onto which ambition—her own and that of others—can be cast. The chart does not moralize this. In the film culture of the 1960s, such sponsorship was intelligible, even normative. Her ascent is curated, contractual, and outwardly propelled.

But Jupiter does not have the final word. The Moon, having passed through Saturn’s absence, Mercury’s radiance, and Jupiter’s projection, next applies to the square of an out-of-sect Mars. In a diurnal chart, Mars stands alone as the malefic outside the solar order, and his malice is heightened. The sequence therefore does not culminate in fulfillment or stability. It ends in rupture. Tate’s life follows this arc with unnerving precision: a gentle childhood without enclosure, a sudden flowering under patronage and marriage, and then a violent termination. Managers and spouses could carry her forward—but they could not carry her past Mars.

Sharon Tate was born on January 24, 1943, in Dallas, Texas, the daughter of a U.S. Army officer whose career required constant relocation. Her childhood unfolded across military bases in the United States and Europe, producing a life of motion rather than rootedness. This itinerant upbringing shaped her temperament: outwardly poised, inwardly private, observant, and emotionally self-contained. Friends later recalled a gentleness that masked a deep reserve—a young woman accustomed to adapting quietly to unfamiliar environments. The absence of a stable home life, and the intermittent distance from ordinary forms of emotional and domestic continuity, fostered both self-reliance and a hunger for belonging that would later express itself through work, partnership, and ambition.

Tate entered the entertainment world almost by accident. While still in Italy as a teenager, she participated in local beauty contests and modeling shoots, drawing the attention of American producers. Her turning point came when she was noticed by producer Martin Ransohoff, the influential head of Filmways. Ransohoff saw in Tate not merely a photogenic presence but a star-in-the-making, and he brought her to Hollywood under contract. He cast her in a series of television appearances and carefully selected film roles designed to introduce her as both glamorous and unconventional. Under his guidance, Tate transitioned from ingénue to emerging screen personality, cultivating an image that blended innocence with modernity.

Her breakthrough arrived with Eye of the Devil (1966) and The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), the latter directed by Roman Polanski. Their professional collaboration quickly became personal. Polanski, already celebrated for Knife in the Water and Repulsion, recognized in Tate a rare combination of beauty, vulnerability, and comic timing. Their relationship was not merely romantic but aspirational: Polanski envisioned Tate as more than a decorative actress, encouraging her toward roles that tested range and presence. He coached her performances, shaped her screen persona, and embedded her within a European-inflected artistic world that contrasted sharply with Hollywood’s studio machinery.

This partnership accelerated her ascent. Valley of the Dolls (1967) earned Tate a Golden Globe nomination and made her a cultural emblem of the era’s fragile glamour. Unlike many starlets, she possessed a self-effacing humor and a willingness to appear awkward, traits Polanski encouraged and that distinguished her from the era’s more stylized icons. Their marriage in 1968 symbolized the fusion of two rising trajectories: the director whose work unsettled audiences and the actress whose promise lay in her capacity to embody both charm and strangeness.

The period coincided with a broader cultural shift. As Polanski was completing Rosemary’s Baby (1968)—a film that transformed domestic intimacy into a site of existential dread—Tate was entering a new phase of her life, pregnant and preparing for motherhood. The film’s release marked a turning point in American cinema, inaugurating a mood of unease that would define the late 1960s and early 1970s. Its themes of betrayal, invasion, and the vulnerability of innocence resonated uncannily with what would follow.

On August 9, 1969, eight months pregnant, Tate was murdered in her Los Angeles home by members of the Manson “family.” She was 26 years old. The crime shocked the nation and became a symbolic rupture: for many, it marked the violent end of the 1960s dream. Tate’s death and Rosemary’s Baby now stand as twin bookends to a cultural transformation—one fictional, one brutally real—both signaling the collapse of postwar optimism and the emergence of a darker American mood.

For decades, Tate’s image remained bound to tragedy. She was remembered less for her work than for the manner of her death. Yet her legacy has gradually been reclaimed. Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) restored her as a living figure rather than a victim: playful, luminous, curious, and on the brink of becoming something more. By reimagining her fate, the film offered a cultural act of mercy, returning to Tate the future history denied her. In doing so, it reframed her place in American memory—not solely as a martyr of violence, but as an emblem of unrealized promise, still radiating the possibility of what might have been.

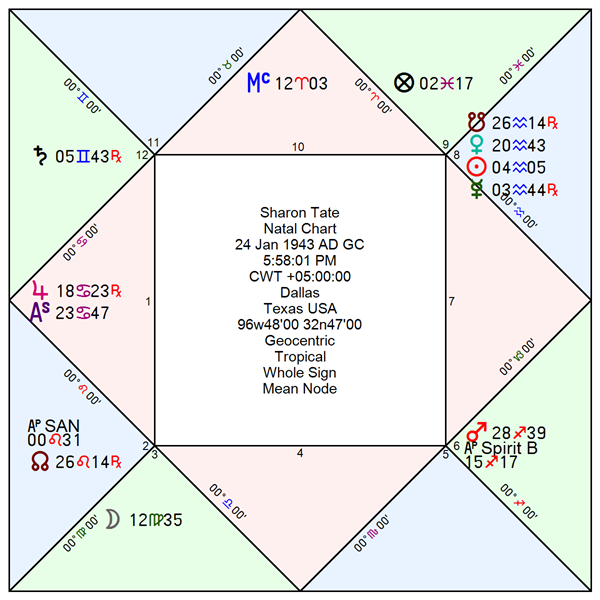

Rodden Rating AA, BC/BR in hand, 5:47 PM, ASC 21CA28

Proposed Rectification: 5:58:01 PM, ASC 23CA47’40”

Complete biographical chronology, rectification and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor model factors favoring Venus/Aquarius

• Bound ruler of Moon, Lot of Fortune, Lot of Spirit

Physiognomy model factors favoring Cancer, Capricorn

Pisces Rising Decan, ruler Jupiter/Cancer-retrograde functions like Jupiter/Capricorn. All cardinal signs have an ovate shape of the face in Willner’s model. This applies for Tate. The center part hairstyle is a Cancer trait and occurs in some photographs. In my opinion, however, Capricorn is a better physiognomy signature for Tate compared to Cancer.

Moon’s Configuration

Sequence:

Moon in Virgo separates from square to Saturn in Gemini retrograde

Sun conjunct Mercury/Aquarius retrograde

Moon in Virgo applies to sextile of Jupiter in Cancer retrograde

Moon in Virgo applies to square of Mars in Sagittarius

Phase I — Moon Separating from Saturn (Gemini, 12th House, Retrograde)

Delineation. Saturn in Gemini retrograde in the 12th house reverses Saturn’s ordinary operation. Rather than imposing limits, it withholds them. Gemini cannot “hold” Saturn in the way Capricorn or Aquarius can, and retrogradation further loosens Saturn’s grip. The Moon’s separation from this Saturn describes a life that begins through the absence of containment: freedom achieved not by protection, but by lack of enclosure. The 12th house activates both the 6th (bodily fragility, illness) and the 12th (isolation, hidden suffering, “evil spirit”), suggesting formative conditions in which ordinary rhythms of care and stability are intermittent or displaced. The Moon moves away from Saturn, indicating a life propelled forward by escaping restraint rather than being shaped by it.

Biographical Match. Tate’s childhood was defined by constant relocation through military postings, a life without a single home base. The pattern accords with Saturn retrograde in the 12th: emotional structures are not imposed; they are absent. She learned adaptability rather than rootedness. This lack of containment did not produce rebellion or bitterness, but quiet self-possession and readiness to move. The Moon’s separation from Saturn describes a girl who does not emerge under authority but past it. Her early life shows no fixed domestic anchor—only forward motion and internal self-sufficiency.

Phase II — Sun Conjunct Mercury Retrograde (8th house)

Delineation. Although not an aspect to the Moon, the inferior conjunction of Mercury is part of the configuration’s texture. Mercury in Aquarius retrograde at inferior conjunction behaves in a solar, performative mode—functionally Leonine. Thought becomes expressive; speech becomes luminous. After Saturn’s absence, the psyche does not retreat into caution; it opens into brightness. The Moon enters a field of warmth and communicative ease. The tone is buoyant, not defensive.

Biographical Match. Tate’s screen presence was defined by lightness rather than severity: self-effacing humor, openness, and a capacity to appear playfully vulnerable. Directors and peers consistently described her as gentle, cheerful, and unguarded. This tonal shift mirrors the configuration. After early non-containment, the personality becomes radiant. She does not carry Saturn’s weight forward. She becomes luminous.

Phase III — Moon Applying to Jupiter (Cancer, 1st house, Retrograde)

Delineation. Jupiter in Cancer retrograde functions as though placed in the opposite sign. Rather than operating through ease, protection, and emotional provision, Jupiter behaves in a Capricornian mode: growth is achieved through effort, projection, and worldly ascent rather than through comfort. The Moon’s application to this Jupiter therefore describes expansion that comes through partners, patrons, and contracts rather than through inner security. Belonging is not given; it is pursued. Advancement is mediated by others. The configuration points to a life in which opportunity arrives through alliance—through those who recognize, sponsor, and amplify the native’s potential.

Biographical Match. What can be established cleanly is sponsorship and amplification. Martin Ransohoff did not merely “discover” Tate; he groomed her deliberately for stardom, placing her in a controlled sequence of television appearances and film roles over several years. Her ascent was contractual, curated, and patronage-based—Jupiter operating through the 7th.

After her marriage, Roman Polanski becomes the second Jupiterian amplifier. He did not simply cast her; he reimagined her range, coached her timing, and embedded her within a more cosmopolitan artistic world. While Polansky was ambitious and sought his own career advancement through Tate, the couple did not suffer the reputation for naked careerism, a common trait of Jupiter in Capricorn. Jupiter here signifies projection, sponsorship, and ascent through alliance.

Phase IV — Moon Applying to Mars (Sagittarius, 6th house)

Delineation. The Moon’s final application is to Mars by square. This is an uncompromising terminus: conflict, rupture, and force. Mars receives the Moon not by harmony but by tension. The life does not culminate in stabilization or repose but in shock. The configuration does not promise longevity; it promises intensity followed by interruption. Mars is the severing blade that ends the sequence.

Biographical Match. Tate’s murder is the literal enactment of this phase: sudden, violent, and irrevocable. The Moon’s arc—from absence of restraint, through radiance, through relational ascent—ends in brutal interruption. The chart does not diffuse this outcome into metaphor. It delivers Mars directly. The biography follows with chilling fidelity: a life propelled forward by freedom and promise, terminated by force.

Interpretive Summary

Sharon Tate’s Moon configuration describes a life propelled by freedom born of absence, not protection. The Moon separates from a retrograde Saturn in the 12th: early life lacks enclosure, producing adaptability rather than containment. She does not emerge hardened; she moves forward unburdened. The inferior conjunction of Mercury then brightens the field, giving her a tone of warmth, expressiveness, and ease. She becomes luminous, not guarded.

Her growth unfolds through others. Jupiter retrograde in Cancer functions as its opposite, routing expansion through alliance rather than inner security. Patronage, marriage, and projection carry her forward—first through Martin Ransohoff’s deliberate grooming, then through Roman Polanski’s ambition for her range and visibility. Her ascent is relational, curated, and outwardly projected.

The sequence does not resolve in stability. The Moon’s final application is to Mars by square. The arc promises intensity and promise, not duration. The biography follows: a life that rises quickly, shines brightly, and ends in violent interruption. The chart does not soften this outcome. It narrates it.

The Influence of Sect

Tate’s chart is diurnal, placing Saturn and Jupiter in sect and leaving Mars out of sect. This distinction materially alters the tone of the entire configuration. Saturn’s in-sect status softens its sting; its already weakened condition—retrograde in Gemini—produces absence rather than oppression. The Moon’s separation from Saturn therefore describes non-containment without cruelty: freedom through lack of restraint rather than hardship imposed. Jupiter, also in sect, renders her ambitious relationships with producers and directors legible within the norms of Hollywood film culture of the 1960s. Advancement through sponsorship, marriage, and projection is not morally aberrant in this context; it is socially sanctioned and culturally intelligible. Mars alone stands outside the solar order. As the out-of-sect malefic, Mars becomes the agent of excess and malice. When the Moon finally applies to him by square, the configuration releases its most violent potential, magnifying the brutality of Tate’s death. The chart thus places harm not at the beginning of life, but at its terminus, where the solitary out-of-sect malefic waits.

Early/Late Bloomer Thesis

Sharon Tate was born after a Full Moon, placing her in a preventional (waning-Moon) nativity. Under the early/late-bloomer thesis, preventional births tend toward late emergence: formative years are quiet, preparatory, or obscured, with visibility and momentum arriving only after a substantial portion of life has elapsed.

Tate’s lifespan ran from 24 January 1943 to 9 August 1969, a longevity of approximately 26.5 years. The midpoint of that span falls at about 13.25 years, in April 1956. Every recognizable career milestone—her discovery by Martin Ransohoff, relocation to Italy and Hollywood, early television work, Eye of the Devil (1966), The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), Valley of the Dolls (1967), her Golden Globe nomination, marriage to Polanski, and rising cultural visibility—occurs well after this midpoint. The first half of her life is largely unmarked by public distinction; the second half contains nearly the entirety of her professional identity.

The pattern fits the preventional thesis cleanly. Tate’s life does not peak early and fade. It gathers slowly, then concentrates its meaning into a brief, luminous arc after the midpoint—exactly the structure expected of a waning-Moon nativity.

AI Notice: This post created with assistance from ChatGPT.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.