William McChesney Martin (1906-1998)

Jupiter in Cancer retrograde: authority, restraint, and the limits of monetary control

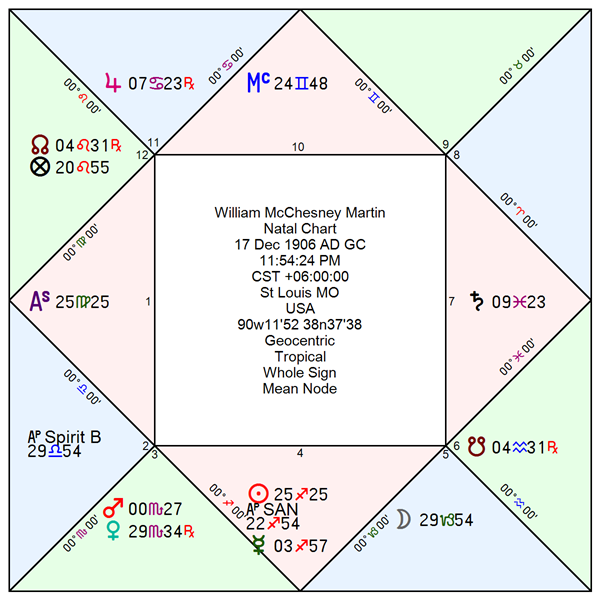

Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin concludes this recent horoscope series with Jupiter in Cancer retrograde and both the Sun and Mercury in Sagittarius, closely mirroring the current sky. As demonstrated in the horoscopes of James Thurber and William Chatterton, Jupiter in this configuration shatters the illusions of Mercury in Sagittarius. For a Federal Reserve chair, this translates into the necessity of crushing inflationary expectations. Martin served as Fed Chair for 19 years, successfully holding the line on inflation for the first 16. In the final three years of his tenure, he lost the inflation battle, overwhelmed by the fiscal demands of Lyndon B. Johnson’s “guns and butter” recklessness—the simultaneous expansion of Great Society programs and Vietnam War spending. This is a complicated horoscope, so it is useful to begin by laying out its structure.

Saturn in Pisces in the 7th house is a weak placement for Saturn, as Saturn’s command-and-control style fails to function effectively in a fluid, boundaryless environment. This is why flooding and powerful hurricanes are commonly associated with Saturn in Pisces (as well as Saturn in the other water signs, Cancer and Scorpio). In Martin’s chart, Saturn in Pisces signifies government officials unwilling to operate within the fiscal constraints required to manage Treasury operations and finance deficits responsibly. Placed in the 7th house, Saturn represents Martin’s open enemies.

Jupiter in Cancer retrograde in the 10th/11th houses is the victor of the horoscope and signifies Martin himself. While Jupiter in Cancer normally favors easy credit conditions for borrowers, Jupiter in Cancer retrograde functions more like Jupiter in Capricorn, imposing a reality check on excessive credit expansion. This is Martin’s famous assertion that the Fed’s role is to take away the punch bowl before the economy overheats. In retrograde motion, Jupiter separates from a trine to Saturn and applies to a trine to Mars, signifying Martin distancing himself from Treasury officials and increasingly advocating tough anti-inflationary rhetoric.

Mars in Scorpio in the 2nd/3rd houses is best read as a 3rd-house placement, given that Martin’s communication strategy—a 3rd-house topic—was consistently tied to anti-inflation messaging. Inflation is signified by mutable signs, with Sagittarius the most inflationary sign of the zodiac, occupied here by Mercury. Mars in Scorpio is 12th from Mercury in Sagittarius by derived houses, making Mars the enemy of Mercury—that is, the enemy of inflation. Notably, the Moon applies to Mars, indicating that this combative, anti-inflation theme grows in importance over the course of Martin’s career.

Venus in Scorpio retrograde in the 3rd house stations direct just a few days after Martin’s birth. For financial markets, Venus retrograde often signifies financial scandal or fraud and its eventual exposure. In Martin’s life, Venus represents the illegalities of the NYSE’s old guard—most famously embodied by NYSE President Richard Whitney—and Martin’s early role as NYSE president in cleaning up those abuses. The Moon’s separation from Venus is consistent with Martin’s NYSE tenure occurring very early in his career.

Mercury in Sagittarius in the 3rd/4th houses, ruling both the Ascendant and the Midheaven, signifies inflation—the issue that ultimately derailed Martin’s personal objectives and damaged his professional reputation during his final three years as Fed Chairman (1967–1970). After the Moon applies to Mars by square, it then applies to Mercury by sextile. This sequence shows that despite Martin’s sustained anti-inflation rhetoric, he ultimately loses the battle, as revealed by the Moon’s full aspect sequence.

The Sun in Sagittarius in the 4th house, near the IC, helps explain why relatively few people today recognize Martin despite his lengthy and consequential tenure as Fed Chair. My teacher Robert Zoller taught that a Sun below the horizon reduces the level of attainable public fame by roughly 50 percent—a principle that fits Martin’s legacy well. This effect appears stronger based on the Sun’s close proximity to the IC.

Finally, the Moon in Capricorn in the 5th house, ruling the 11th, signifies Martin’s deep concern with currency stability, Treasury operations, and balance-of-payments issues. At times, these concerns diverted his focus away from a singular, uncompromising fight against inflation.

Now let us turn to the man himself.

William McChesney Martin, Jr. (1906–1998) was the central banker who defined the modern Federal Reserve, serving from 1951 to 1970—longer than any other chair—and stewarding U.S. monetary policy across five administrations. Born into a St. Louis banking family, Martin was exposed early to the intellectual and political debates over central banking; his father had helped draft the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. After Yale, Martin entered finance and rose rapidly on Wall Street, displaying both unusual maturity and a deep respect for institutional integrity. These qualities crystallized during his early career at the New York Stock Exchange, where he played a decisive role in one of the most dramatic scandals in NYSE history: the fall of Richard Whitney.

Richard Whitney, the patrician and highly respected NYSE president, was widely believed to embody Wall Street’s prestige—until whispers of irregularities grew too loud for Martin to ignore. As a young NYSE governor and later head of its governing committee, Martin pressed for an internal inquiry into Whitney’s finances. Quiet but relentless, Martin followed accounting discrepancies that revealed Whitney had been borrowing heavily, misusing customer funds, and engaging in outright fraud to prop up his failing brokerage. Martin insisted that the Exchange confront the truth, even against fierce resistance from Whitney’s allies. His investigations ultimately exposed the full scope of Whitney’s misconduct, leading to Whitney’s arrest, conviction, and imprisonment in 1938. At age 31, Martin was elevated to president of the NYSE—its youngest ever—largely because he had demonstrated the courage to cleanse the institution from within. This episode forged his lifelong ethos: public trust requires unwavering honesty, even when powerful interests resist.

Martin’s reputation for integrity and steadiness brought him into government service during World War II and later into a pivotal role in one of the most consequential financial negotiations in American history—the 1951 Treasury–Federal Reserve Accord. During the war and its aftermath, the Fed had been required to keep interest rates artificially low to support Treasury financing—effectively subordinating monetary policy to fiscal needs. By 1950–51, inflationary pressures from the Korean War made this arrangement untenable. As Assistant Secretary of the Treasury and later as the negotiator representing the Federal Reserve, Martin worked to craft an agreement that would restore the Fed’s independence while preserving government financing flexibility. The result was the historic Accord of March 1951, which freed the Fed from mandatory interest-rate pegging and reestablished its authority to conduct anti-inflationary policy. Truman selected Martin as Federal Reserve Chairman immediately afterward—an ironic twist, as Martin had helped negotiate a deal that the White House had reluctantly accepted. Martin took office as the embodiment of the newly independent central bank, determined to protect the hard-won autonomy he had helped create.

Nowhere was this tested more dramatically than in Martin’s confrontation with President Lyndon B. Johnson, a defining moment in the political history of the Federal Reserve. In late 1965, with the Vietnam War expanding and domestic spending rising under the Great Society programs, inflation pressures were mounting. Martin believed that a pre-emptive rate increase was necessary to preserve long-term stability. Johnson, facing political and fiscal strains, strongly disagreed. When the Fed raised rates anyway, Johnson summoned Martin to his Texas ranch. There, in an episode that became legend, LBJ threw his arm around Martin, walked him outside, and berated him privately—what Martin later described as being taken “to the woodshed.” Johnson insisted that tighter money would undermine national unity during wartime and accused Martin of disloyalty. Martin, shaken but unmoved, defended the independence of the Federal Reserve. The confrontation became the canonical example of political pressure on U.S. monetary policy—and of Martin’s determination to resist it. Though Johnson extracted a temporary cease-fire, Martin remained committed to guarding the Fed’s autonomy and repeatedly warned of rising inflationary dangers that history proved well-founded.

The broader record of Martin’s inflation management reflects both his greatest success and his most enduring controversy. The Treasury–Fed Accord and his willingness to confront Lyndon Johnson demonstrated a deep institutional commitment to central bank independence and anti-inflationary discipline. From 1951 through roughly 1965, Martin presided over a period of remarkable price stability, guiding monetary policy through postwar demobilization, the Korean War aftermath, and sustained economic expansion without allowing inflation to become entrenched. During this era, the Fed routinely leaned against excess demand, tightened preemptively, and maintained credibility in financial markets. However, beginning in 1966, the policy environment deteriorated sharply as fiscal pressures from the Vietnam War and Great Society programs overwhelmed the Fed’s traditional tools. Martin increasingly sought coordination with Congress and the White House, most notably gambling in 1967 that delayed monetary tightening would induce passage of a tax surcharge. When Congress failed to act promptly, the Fed was left having eased too much for too long, allowing inflation expectations to reaccelerate. The eventual tax increase in 1968 came late, forcing the Fed into aggressive catch-up tightening in 1968–69. This stop-go pattern—sharp restraint followed by easing and then renewed tightening—destabilized markets and helped set the stage for the inflationary psychology of the 1970s. Though Martin remained intellectually opposed to inflation, political constraints, institutional caution, and his faith in fiscal partnership ultimately limited his effectiveness in the final years of his tenure, tarnishing an otherwise distinguished record.

Martin retired in 1970 after nearly two decades of service, having shepherded the central bank through the postwar boom, military conflicts, the early unraveling of the Bretton Woods system, and increasing political pressure for easy money. His famous metaphor—that the Fed’s job is to “take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going”—summarizes his philosophy of pre-emptive discipline in an economy prone to excess. He died in 1998, widely regarded as the model of an independent central banker—honest, cautious, principled, and willing to stand alone when necessary.

No Astrodatabank record

Initial Rectification: 18-Dec-1906, 12:16:35 AM, ASC = 29VI55’15”

Revised Rectification: 17-Dec-1906, 11:54:24 PM, ASC = 25VI25’13”

Rectification Note: This has been a tough rectification. Even with the initial rectification, I made a note that ZRS was a much better fit for the LOS in Libra, not in Scorpio. Initially I was hesitant to make this choice because it moved the Moon from early Aquarius to late Capricorn. Why? Because those with a Capricorn Moon often demonstrate an affinity for military culture and Martin did not fall in this cohort. And yet, with Moon in Capricorn ruling the 11th of currency and Treasury, the ability of the Moon’s primary directions to consistent time balance of payments problems and a major Sterling devaluation convinced me of the merits of a late Capricorn Moon.

Complete biographical chronology and time lord studies available in Excel format as a paid subscriber benefit.

Victor Model factors favoring Jupiter/Cancer – retrograde

Sign ruler: Sun and Prenatal syzygy

Bound ruler: Lot of Fortune

House of Joy

Empirical match of Jupiter minor Firdaria periods to ‘taking away the punchbowl’ episodes.

Physiognomy Model factors favoring Taurus

Shape of face is the soft rectangle of Taurus according to Willner’s facial shape-sign model.

Rising decan is Taurus ruled by Venus/Scorpio – retrograde functioning like Venus/Taurus.

Moon’s Configuration

Phase I — Moon separating from Venus (Scorpio, retrograde, 3rd hosue)

Delineation. The Moon’s final act in Capricorn is its separation from Venus retrograde in Scorpio, a configuration that immediately frames Martin’s emotional and professional orientation as reactive to corruption, moral decay, and institutional imbalance. Venus retrograde in Scorpio signifies compromised values, hidden financial entanglements, and reputational rot within elite systems. The Moon’s separation indicates a life trajectory defined by exiting a corrupted Venusian environment rather than benefiting from it. This is not Venus as patronage or harmony, but Venus as scandal exposed, trust violated, and prestige hollowed out. The Capricorn Moon responds by assuming responsibility, order, and authority in the aftermath of decay.

Biographical Match. This configuration precisely describes Martin’s role in uncovering the financial fraud of Richard Whitney at the New York Stock Exchange. Whitney, a Venus-in-Scorpio figure par excellence—aristocratic, secretive, and financially compromised—embodied the Exchange’s hidden rot. Martin’s relentless investigation and insistence on institutional accountability culminated in Whitney’s disgrace and imprisonment. The Moon separating from Venus corresponds to Martin’s removal from a tainted financial order and his subsequent elevation as NYSE president. His rise was not achieved through Venusian favor but through the rejection and cleansing of corrupted Venusian authority.

Phase II — Moon changes signs: Capricorn → Aquarius

Moon conjunct South Node (4°31′ Aquarius), Moon in the bound of Mercury

Delineation. The Moon’s ingress into Aquarius is dominated not by the sign itself but by its immediate conjunction with the South Node which intensifies lunar sensitivity. The Moon’s placement in the bound of Mercury further intellectualizes this anxiety, making instinctual responses overly mediated by analysis and language. Aquarius fixes attention on systemic order and long-term structure, while the South Node exaggerates caution and risk-aversion. With bound ruler Mercury in Sagittarius, concern about inflation, expansion, and excess becomes the Moon’s central emotional fixation. The result is a temperament perpetually alert to price instability and macroeconomic overheating.

Biographical Match. This configuration describes Martin’s deep and persistent preoccupation with inflation throughout his career. From the Treasury–Fed Accord onward, Martin’s instincts were shaped by a fear of repeating historical monetary failures. His vigilance was not episodic but structural—an ever-present internal warning system. The South Node’s influence explains why inflation loomed larger for Martin than other economic concerns, even during periods of relative price stability. His Mercury-bound Moon made him analytical, communicative, and institutionally minded, while Mercury in Sagittarius oriented those qualities almost obsessively toward inflationary dangers. This helps explain both his early success and his later over-caution.

Phase III — Moon applying to square Mars (Scorpio, 3rd house by whole sign)

Delineation. The Moon’s application to a square with Mars in Scorpio introduces conflict, combativeness, and urgency into the emotional narrative. Mars in Scorpio is relentless, strategic, and uncompromising, especially when directed toward perceived existential threats. By derived houses, Mars stands as the twelfth from Mercury in Sagittarius—an unseen enemy to inflation, signifying hidden battles fought through pressure, signaling, and confrontation rather than spectacle. The square aspect denotes strain: the Moon must struggle to act on its convictions. This is not easy assertion but disciplined, often lonely resistance.

Biographical Match. This phase maps directly onto Martin’s aggressive anti-inflation messaging and his willingness to fight inflation even when politically costly. His confrontations with Lyndon B. Johnson exemplify Mars in Scorpio: private, intense, and adversarial rather than theatrical. Martin’s communications—rate hikes, warnings, testimony—were weapons deployed against inflationary forces he viewed as dangerous and destabilizing. The square reflects the friction between his instincts and political reality; his battles were real, but never clean victories. This phase defines Martin as a central banker who fought inflation, even when the fight strained alliances and authority.

Phase IV — Moon applying to sextile Mercury (Sagittarius; 4th house, ruler of ASC and MC)

Delineation. The Moon’s final application is to Mercury in Sagittarius, ruler of both the Ascendant and Midheaven, tying emotional resolution directly to identity and public standing. The sextile suggests opportunity and intention rather than compulsion, yet Mercury’s condition is inflationary, expansive, and ideologically driven. As ruler of both personal aims and reputation, Mercury signifies that success or failure will be publicly interpreted through the lens of inflation management. The Moon’s application indicates an attempt to reconcile instinct with doctrine, but also a vulnerability: if Mercury fails, both personal objectives and legacy suffer.

Biographical Match. This final phase accurately reflects Martin’s own judgment of his career. Despite decades of service and early success, Martin viewed his chairmanship as ending in failure because inflation accelerated during the late 1960s. As inflation rose, so too did criticism of his leadership, damaging his reputation and undermining the very objective—price stability—that defined his identity. The sextile shows effort and intention, not inevitability; Martin tried to align policy, communication, and institutional authority, but the outcome fell short. His legacy, like this final application, is mixed: principled, serious, and historically consequential, yet marked by unresolved inflationary pressures at the close of his term.

Interpretive Summary

William McChesney Martin’s Moon configuration describes a temperament shaped by institutional responsibility, moral vigilance, and an enduring sensitivity to inflationary risk. The sequence begins with a decisive separation from corrupted Venusian authority, establishing a lifelong pattern of cleansing rather than accommodation. The Moon’s ingress into Aquarius is decisively shaped by the South Node, producing an ingrained caution and historical memory that magnified inflation concerns above all else. Mars in Scorpio supplies the will to fight—often privately and at great personal cost—while the final application to Mercury in Sagittarius binds Martin’s identity and reputation to inflation management itself. The result is a career defined not by complacency, but by disciplined anxiety: a central banker who saw inflation clearly, opposed it forcefully, yet ultimately judged himself by its resurgence at the end of his term.

Early/Late Bloomer Hypothesis

William McChesney Martin was born in 1906 and died in 1998, giving him a lifespan of 92 years and a midpoint at approximately 1952–1953. By that midpoint, Martin had already achieved the defining milestones of his life, strongly confirming him as an early bloomer in the classical waxing-Moon sense. He had risen to president of the New York Stock Exchange at age 31, exposed and dismantled the Richard Whitney scandal, served in senior wartime and Treasury roles, negotiated the 1951 Treasury–Federal Reserve Accord, and was appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve immediately thereafter. Most importantly, by the early 1950s he had already established the institutional framework and personal authority that would define U.S. monetary policy for the next two decades. His later career, while longer in duration, largely consisted of maintaining, defending, and refining structures that had been created before the midpoint of his life, a hallmark pattern of early-blooming nativities.

AI Notice: This post created with assistance from ChatGPT.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to House of Wisdom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.